Even amidst all the visual detritus of our cluttered contemporary media landscape, the indelible imprint of Mike Mills retains visibility, be it in his nakedly subversive graphic designs, T-shirts, album covers and music videos for Air, Sonic Youth and Moby, commercials for Nike and Levi’s, or emotionally charged documentary films of post-modern dislocation. Add to these his stockpiled anti-establishment street cred as legendary member of the Alleged Gallery and co-founder of the Directors’ Bureau, boasting members like Spike Jonze and Sofia Coppola, and it comes as no wonder that Mills is so widely hailed as the revolutionary indie-punk master of multi-media artistry.

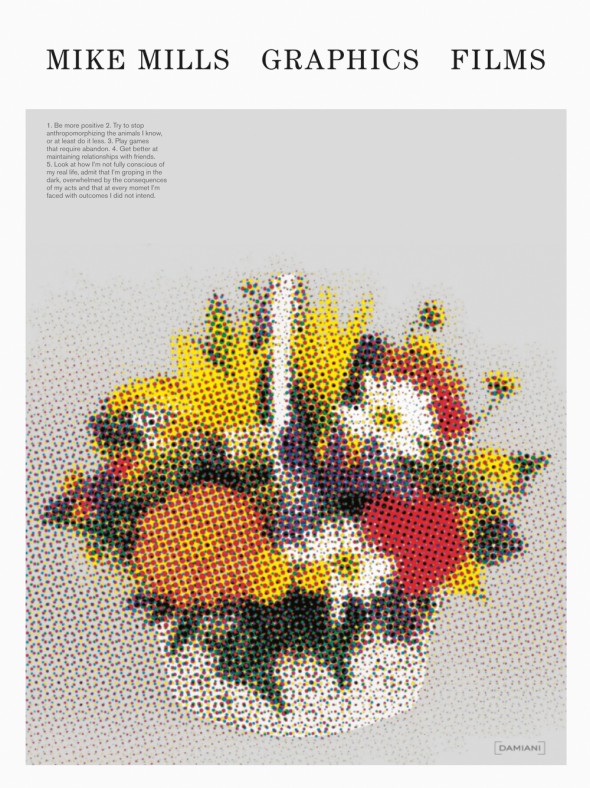

Mike Mills: Graphics/Films, the first collected retrospective of his prolific career, follows no chronological or genre-specific ordering, but appears a random mélange of Warholian pop-cult iconography, 1970s minimalism, blunt typography, satiric subversion and parodied cultural nuance, united only as a successive series of attempts at reconciliation. His innumerable projects running the entire media gamut differ only in format, but, in fact all constitute formulations of the same experiment, each transmitting the voice of post-Gen X adolescent angst.

All of his works bear the distinctive mark of anarchic void — an intentional absence of linearity, symbolism, or resolution. Proffering no definitive message or didactic moralizing, bereft of stylistic signifiers, they are studies in reduction, distillations down to seeming nothingness that nonetheless resonate emotion — a naked documenting of psychic agitations, hiccups of the soul. One poster reads “This is coming of age? Facing that we’re not like the dreams we have of ourselves ideas of adulthood a fradulent myth why not just stay in a world of infantile fantasy maybe forever even.”

The tome then takes shape more as a retrospective of the struggling adolescent spirit, the uncertain product of an excessively commodified world. That he finds a unity in multiple mediums, oscillating between segmented spaces of genre, medium and corporate industry, and designates the public sphere as the ultimate space for deeply personal expression, is reflective of the contemporary consumerist multi-media landscape in which he was raised. And that he views adolescent struggle and disquietude as concomitant with that of the dejected philosophizing of the urban punk-skate-graffiti subculture in which he’s remained creatively steeped is likewise reflective of his world. To Mills, the Beat Generation persists in the artists of today’s skate-punk underground, “down and out,” as Kerouac depicted, “but full of intense conviction with a melancholy sneer, not juvenile delinquents but characters of a special solitary spirituality staring out the dead wall window of civilization.”

And in adolescence, he perceives a disillusioned recognition of contemporary cultural chaos and ruptured existence that bespeaks the clear-eyed lucidity of post-modern enlightenment. Thus, the self-proclaimed eternal punk adolescent perceives each project as “the antidote to the one before,’’ a disorderly progression of deeply introspective experiments, personal exercises in battling his own inner demons.

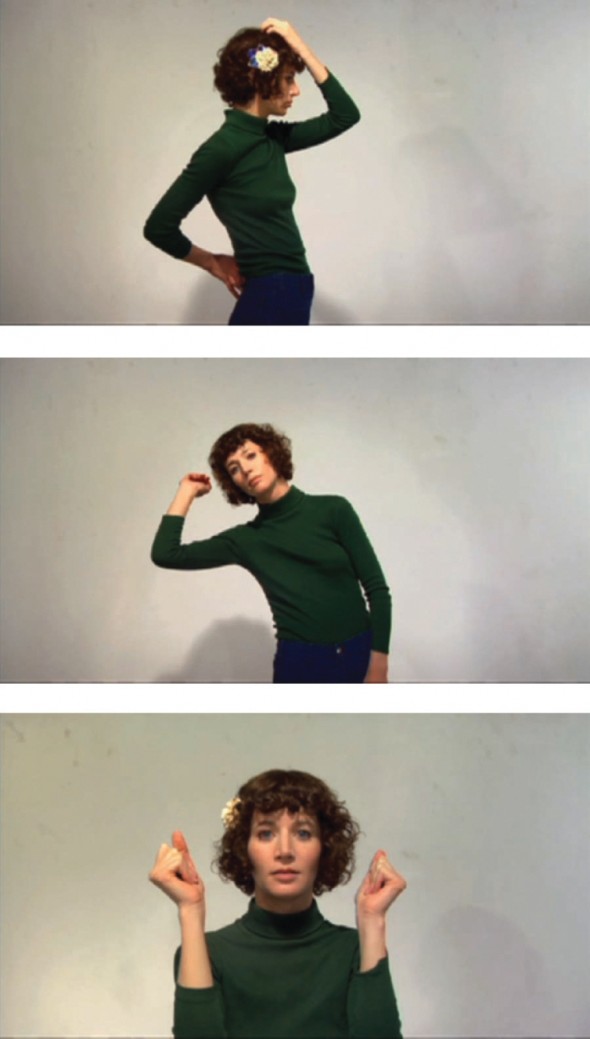

Mills’ intensely intimate confrontation with maturation’s dissolution of childlike fantasies of the self, his simple visual amalgamations tempered with the modern malaise of loneliness, alienation, insecurity and disillusionment are recreations of naïve experience, of seeing for the first time, a return to the purity of adolescent sight & inquiry, where his voice from the periphery becomes audible as somewhat of a hopeful detour from punk’s dystopian legacy.

— Kevin Kincaid