Text by Alexander Provan

Photography by Kenichi Hagihara

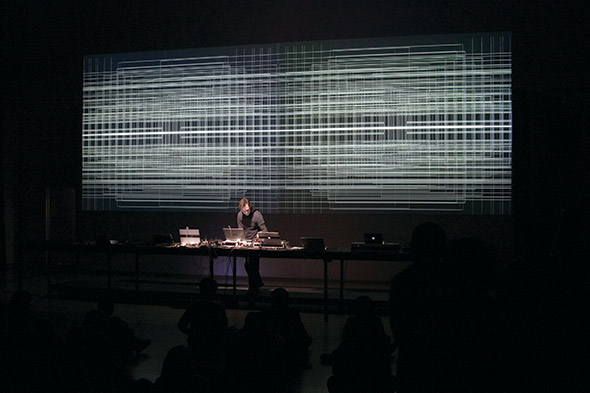

Carsten Nicolai’s performance of Xerrox in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in May was as much surgery as music. An array of computers and mixers replaced the patient on the operating table, and rather than display the surgeon’s forays into the body, a vast screen behind Nicolai burst with clusters of golden particles. As the sounds came into focus and coagulated – abstracted bits of muzak, ringtones and advertisements reduced to the point of incomprehensibility – it became clear that Nicolai was raiding the body rather than repairing it, gradually extracting failed nerve endings and fractured sine tones to create a noisy opus of error messages.

Performing as Alva Noto, Nicolai has been mining and designing sound for the better part of his 41 years, ever since hearing the ghosts of Soviet military signals seep through his radio as a child in East Germany. His work is generally sparse and glacial in pace. Orphaned frequencies and aborted pulses are placed under the microscope, deliberately manipulated and combined with other specimens. On 2001’s Transform, buzzing frequencies are treated like toothpicks, delicately molded and shaped into tenuous structures. If bent too far in one direction, they will splinter. They often do.

Nicolai has established himself as a major force in contemporary art, performing and exhibiting multimedia installations across the world, from the Biennale in Venice, the Guggenheim in New York and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Besides his sound production, Nicolai also runs the Raster-Noton record label which has released his own work.

In “Atem,” his Liverpool Biennial exhibition, the combined effects of subsonic bass rumblings and visitors’ footsteps produced intricate patterns on the flasks of water on the ground. His recent collaborations with Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto reconciles circuitry and empathy. Nicolai bends and shades Sakamoto’s melancholic piano figures, and resists doing much else. The effect is like a broken two-way radio and a toy piano playing a duet in an empty stadium. Notes don’t end as much as they float into space, while Nicolai’s own drawling tones just hover, changing imperceptibly over five or 10 minutes. There are contours that can barely be distinguished, walls and windows built from timbre and resonance rather than steel and glass. The structure exists for 30 or 40 minutes, then Nicolai turns off the computers and the walls vanish.