Text by Yon Motskin

“It is often said that when people grow old they become children again,” director François Ozon said recently about his latest film Time to Leave. The tough, love-loss drama is the second in the French filmmaker’s “trilogy of mourning” that began with Under the Sand, and though it treads similar water as that critically acclaimed Charlotte Rampling vehicle, the new film doesn’t dive nearly as deep.

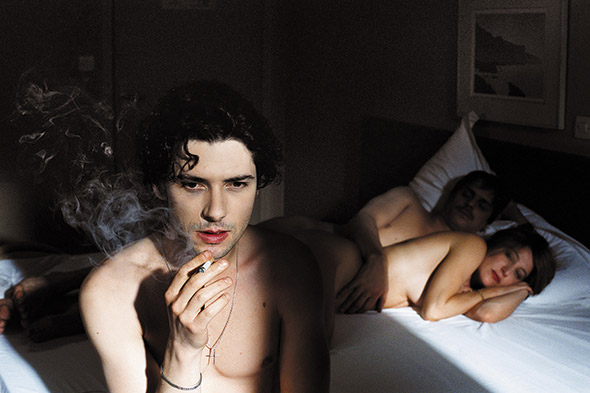

Time to Leave is a character study of Romain, a handsome 30-something fashion photographer who discovers that he has terminal cancer. With only months left to live, Romain refuses both treatment and sympathy, not revealing his fatal secret to anyone – not his co-workers, parents, sister or even his boyfriend. Romain sets out on a literal and spiritual journey to alienate everyone – including himself – before he dies. The question that the film poses is perplexing. Time to Leave doesn’t ask how he will spend his last days, but rather, “Why would somebody spit in the faces of friends and family when the end comes?”

Like many contemporary filmmakers, Ozon took a familiar framework – the ’50s Douglas Sirk melodrama – and reinterpreted it with his interests in mind. In this case, it’s homosexuality, photography and grief. He cast a hard, unsympathetic Melvil Poupaud (a popular French actor familiar to American fans from Le Divorce) in a role that begs for sympathy but pushes it away from every close-up. Since Romain’s fate is definite from the first scenes, there is little tension or suspense to hold us for 80 minutes. Like a child, Romain seems to hate everyone, and in turn we begin to hate him for it. Particularly nasty is when he chews out his sensitive sister Sophie who also happens to be a single mother, kicks out his longtime layabout boyfriend Sasha, and insults Jany, a vulnerable stranger (Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi) who later offers him a unique proposition in exchange for his secret. How much pity and self-loathing can one man suck from an audience?

And then Jeanne Moreau lights up the darkness. The luminous muse of the French New Wave plays Romain’s grandmother Laura, whom he visits on his last hurrah. On a short road trip from Paris, he spends a night at her country house, and these few and simple scenes make the film momentous, like a warm breeze in Ozon’s otherwise cool draft. The bitter, biting Romain that we’ve seen up until now melts away and becomes more honest and vulnerable. He confides his secret to her because they are the same, and we immediately see why. She doesn’t baby him, she doesn’t pity him; she understands and loves this complicated person in a way no man, woman or audience member might. Their relationship never physically goes beyond a grandson-grandmother intimacy, but that it would be believable (and enjoyable) if it did, is a testament to the sex appeal of the Jules and Jim septuagenarian. Those lips! Those eyes! That sadness!

The end of Time to Leave is not much of a surprise; like many of Ozon’s films, we start and finish with the sea, a sign of purity and timelessness. But Ozon employs other motifs which are equally memorable. Interspersed throughout the film is a fresh-faced young boy, presumably Romain as a child. Or perhaps it’s an idyllic memory of his. Regardless, Romain witnesses his younger self grow up as his older self deteriorates, climaxing with their brief, wordless confrontation on the beach. Another interesting method Ozon uses to express the oppression is Romain’s picture-taking – the photographer jettisons his professional stock for a simple point-and-click, and each photograph he shoots takes on superlative meaning as it may be his last.

Where Time to Leave fails is where Under the Sand succeeds. The latter film is suffused with mystery, as it features a woman who grieves for her missing husband after he ostensibly drowns in the ocean. Did the husband die, or did he simply leave while his delusional wife just missed the signals? That the question is never fully answered is part of the film’s wonder and uniqueness, and with it, Ozon creates a kind of open-ended mourning. So when do you stop hoping and start mourning? In Time to Leave, Romain’s death is imminent and definite, and his grief is more straightforward: it is entirely his own.

Moreau has said that she considers Ozon not a metteur en scène – i.e. a filmmaker who simply organizes – but a réalisateur, a director who passionately and personally turns his imagination into something real. It’s hard to argue with Moreau, an actress who’s worked with such masters as Truffaut, Godard, Buñuel and Fassbinder. But does Ozon compare to those legends? He is certainly ambitious, releasing nearly a film a year since his acclaimed short See the Sea nearly a decade ago, a filmography that includes Swimming Pool and the campy misfire of 8 Women. But several other exciting new French filmmakers have emerged in the last few years to challenge Ozon’s place in contemporary film, such as Gaspar Noé (Irreversible) and Jacques Audiard (Read My Lips and The Beat That My Heart Skipped). So don’t go placing the title of the Next Big Thing on anyone’s head just yet – but be sure to keep your eye on Ozon.