A photographer’s lens sheds light on Russia’s lethal legacy

Like lands ravaged by the rains of Chernobyl, many of the sites National Geographic photographer Gerd Ludwig visits aren’t just unpalatable to the average traveler—they’re dangerous. Cutting, haunting images of the abandoned and blighted regions left behind in Chernobyl’s wake have become Ludwig’s trademark, and the people who continue to live there, his cause. From the relative idyll of his Los Angeles home, he shares with us why he keeps returning to the fallout zone.

The Russian government keeps journalists on a short leash—yet your work exposes some very unflattering sides of the country. How were you able to get such access?

My first trip to the Soviet Union was in 1980, so I’ve known the current system from the very beginning. Having continued to work through its transformations as a constant visitor, I’ve been able to adapt to the changes in getting access. However, it is still very difficult to gain access into many areas.

So you’ve had brushes with the law.

I’ve been detained briefly in Russia at least a dozen times. I personally don’t feel threatened that much. There’s so much red tape there that, generally, the officials and militia won’t dare to touch foreigners. The most threatening part is when they’re trying to get to the Russians that work for me. They are most in danger in that situation.

How did you first become interested in covering Russia?

When Hitler annexed Czechoslovakia, my father found himself going from being a Czech solider to a German solider the next day. He was among those who invaded the Soviet Union and fought in Stalingrad. After the war, my father told me stories that I originally thought were bedtime stories. Only later I understood that these stories of people hiding from soldiers in snowstorms, in barns and stables, were my father’s attempt to rid himself of the horrors of war. So I had images in my mind of Russia before I even knew the country existed. Later, as a member of the first postwar generation of Germans, I felt incredibly guilty for the deeds of my parents’ generation and started to idolize everything Russian.

Your pictures capture the desolation of Chernobyl and the abandoned city of Pripyat—yet somehow they’re beautiful. How do you balance beautiful composition with tragic content?

I think that good composition in a picture can be simply compared to the good grammar of a writer. The composition is just a way to make people look at the content. An image has to be composed in the right way to convey such destruction.

How do you connect with your photographic subjects, many of whom are suffering or dying from horrific fallout-related diseases?

As National Geographic photographers, we take our cameras and our readers to often uncharted areas, not only physically, but emotionally. We do that out of a deep commitment to important stories told on behalf of otherwise voiceless victims. Those people are really my heroes, because they have allowed me to photograph them in the simple hope that, with greater awareness, tragedies like this may be prevented in the future.

Why is it that you live in L.A. and work in the Ukraine?

My ex-wife chose to relocate us from New York while I was out on assignment, but Los Angeles has grown on me, and, you know, it is so nice to come back to Los Angeles. It always feels like being on vacation.

Don’t you ever want do to shoot someplace pleasant, like Tahiti?

How boring. That would be awful. After so many grave and exhausting assignments in Russia, when National Geographic said to me, “You deserve to shoot a long assignment in Hawaii,” I said: “No, please don’t punish me.”

-Gabriel Bell

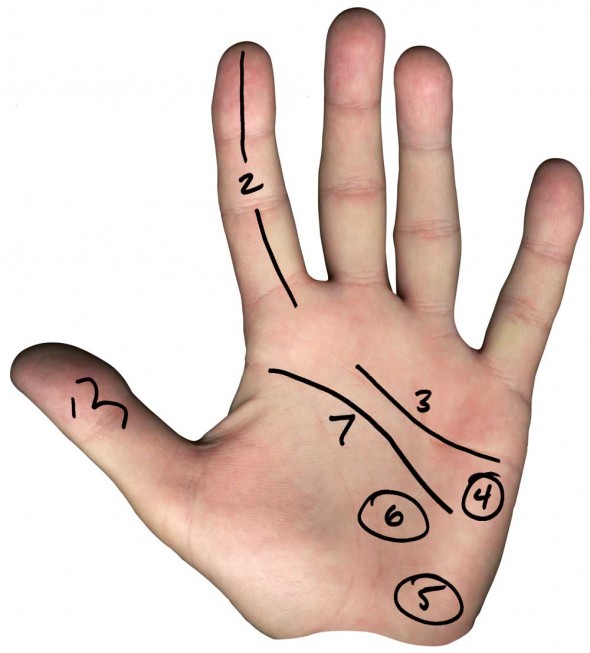

Reading by Lena, who has no idea this palm belongs to Gerd Ludwig

1. Gets ahead of himself. This is not a person to predict will meet you for lunch in Paris on the third of the month as planned. Instead, he’ll be in a bistro in Timbuktu, wondering where you are and why you’re not there.

2. Extremely intelligent. A tendency to headaches when trapped in circular logic over minutiae.

3. Emotionally and romantically attracted to independent free-thinkers who value communication.

4. A love of travel—the byways, NOT the highways, with a tendency to get lost on those byways, arriving somewhere very interesting, though not the intended destination.

5. Somewhat accident-prone while traveling and does not retain luggage very well.

6. An avid collector of bizarre items, some of it bordering on the macabre.

7. A thinker and a planner, but also very impulsive! He makes detailed plans and itineraries, but doesn’t follow them, yet gains much of value along the way.