Magicians are hard to come by these days. Sam Bompas and Harry Parr, however, have achieved just that: magic. And they have done so with the least imaginable medium.

Their jelly creations have taken over London, their hometown. They have many times recreated these masterpieces in rainbow-hued gelatins and are now making waves all over the world. Their company, Bompas & Parr, was launched in 2007, when they applied for a space to sell jellies at a popular London food market. The application was denied, but they managed to cater for a few parties to get started. They were soon noticed by the Sunday Times and were included in a roundup of traditional English cuisine. It wasn’t long before business skyrocketed.

“No one was making jelly, so there was an obvious gap in the market,” they explained. “Our inspiration came from two sources: childhood nostalgia and the knowledge that England used to be famous in the culinary world for two things: jelly and roasting.”

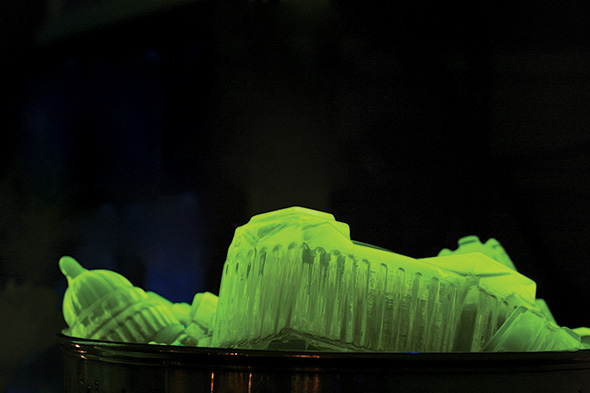

And in their food spectacles they have achieved the best combination of tradition and wow-ness: nothing seems impossible, from a glow-in-the-dark jelly to a gelatinous reproduction of the Barajas Airport (to date the favorite architectural project of the duo). In an early quest to get molds for their jellymaking (molds are very expensive and hard to find, they explained), they invited world-renowned architects to design molds for them, resulting in one of the craziest gastronomic collaborations seen to date. The architects they worked with include Lord Foster, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (creators of the aforementioned airport) and Nicholas Grimshaw, whose works were replicated in wobbly improbable colors.

When explaining their fascinations for jelly and its application to architectural structures, they quoted Professor Stephen Gage from the Bartlett School of Architecture at the University College London: “As babies, we first learn about our world by touching it and putting bits of it in our mouth. Part of our subconscious appreciation of shape may well be a dim memory of how it might feel in our mouth. Thus a dome is round and coolly satisfying, while a pointed building is like a sharp and dangerous knife. Jelly architecture returns architecture to the mouth, where we can once again taste it.”

Nobody can resist a smile in front of a jelly, they said, and the unstable wobbly factor is key to the fun. Difficult as it is, however, they found the perfect compromise between flavor and structure.

Their experiments with foodstuffs don’t stop at jellies. In 2009 they filled a room with cocktail fog for visitors to inhale, and earlier they devised a 12-course Victorian Breakfast (4,000 calories a head) commissioned by Warwick Castle.

Their creations are like charming translucent ghosts, and their approach to food is exceptional: the amount of research and care to detail that goes into each of their projects is incredible, and their attention to the history of food is fascinating. So much so that they have gained the attention of London’s food master, Chef Heston Blumenthal, a fan since the start, and have been asked to curate two books about their work (Jelly with Bompas & Parr came out in 2010, while Cocktails with Bompas & Parr hit shelves two months ago to include recipes, stories and incredible pictures).

Their curious projects continue, and as an ultimate (short-term) goal, they are setting out make the biggest jelly in the world: “It would be the size of a small castle.”

TEXT BY Rosa Maria Bertoli