Photography Trevor Good

With the rise of the figure of the freelance curator, curating has ventured out of the museum into galleries and beyond—to the extent that those who take themselves to be on the very edge of hip go so far as to claim that they “curate” menus and music playlists. Architecture writer and curator Carson Chan is more rigorous with his terms, sticking to the exhibition-making aspect of curating. “Curating should not be equated with mere selection or organization,” he clarifies, “it is the spatial contextualization of cultural material. Curating gives an audience access to these materials.”

Where he sees potential for curating lies in treating space as a material for making exhibitions. With a background in the history and theory of architecture, Carson’s curating emphasizes an architectural notion of space. “Architecture is not the same as buildings,” he warns, a truism good to be reminded of considering that most people experience architecture on a much more casual level than film, music or literature, for example. Architecture encompasses not only technical design, but also the social and aesthetic dimensions of human-constructed spaces. Carson places architecture in dialogue with curation via the trope of the exhibition: “The exhibition is a cheaper, more accessible way of communicating architecture without building a building,” he says. “In an exhibition people experience space on a one-to-one level, and it is my goal to enforce a kind of spatial fluency.”

Carson’s current show, Stronger Magic at the Grimmuseum in Berlin, attempts to materialize the increasingly palpable collapse between the virtual and the real that the ubiquity of the Internet has brought upon contemporary world views. Along with Aaron Moulton, the two have set up an experimental platform billed as The Curators Battle: 2 curators, 2 shows, the same artists, which puts their work in dialogue with one another without being a traditional collaboration on one show.

Photography by Laura Gianetti

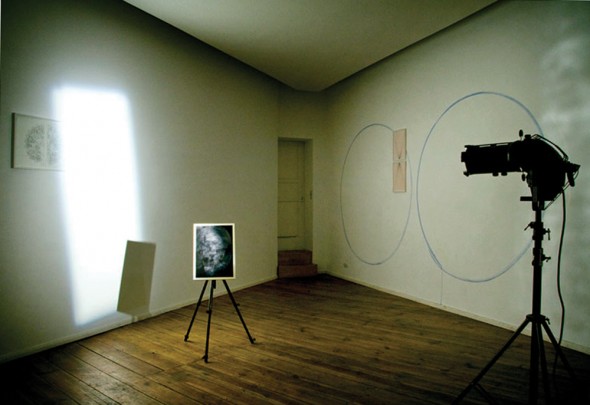

Stronger Magic possesses an exacting sense of space. Or to put it as simply as possible: the experience that Chan creates is not a collection of more or less interesting objects crammed into a room in the name of contemporary art. Instead, Stronger Magic elicits the feeling of objects and bodies mutually belonging to a space. Parallel to the curator’s perennial concern about the placement of artworks in relation to one another in group shows—provocatively, considerately or otherwise, always at the risk of either overemphasizing or obfuscating artist authorship—is lighting. In Stronger Magic Carson thwarted a high-paced economy of attention by creating two distinct shows within the exhibition. One was fully illuminated. The other was in the dark, where an actual artwork, Darri Lorenzen’s “Undefined” (2011), a pulsating stage light, illuminated the constellations of artworks in the room at soothing intervals. On the way to the light and placed on high, as if an altar, was Constant Dullaart’s “The Sleeping Internet,” a monitor displaying a Google page with the search “breaking news” that self-updates and fades in and out, visually inhaling and exhaling at the rate of a sleeping human. And in broad gallery light was Timur Si-Qin’s “Selection Display” (2011), two enlarged cardboard stock photos of a female Asian hair model. All of the works addressed the Internet, and Carson’s take on the space and its lighting, its theatrically, as it were, further materialized what it is to inhabit a world defined by the hazy dualism of the virtual and the real.

Upon arrival in Berlin in 2005, Carson worked as an architect at Barkow Leibinger Architects and then moved on to the Neue Nationalgalerie’s architecture exhibitions department. In 2006, he and collaborator Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga founded PROGRAM, a project dedicated to exploring emerging processes at the intersection of art and architecture. In an art world in which lax theorization has itself become an aesthetic, Carson shines as a skilled thinker and writer. Recent writings dealing with space as a curatorial material and art in the digital age appeared in Fillip (Vancouver) and Kaleidoscope (Milan), respectively. He has also been appointed to co-curate the Marrakech Biennale in 2012.

“What is contemporary anyway?” I ask.

“Anything happening right now. But the contemporary in art has a look, an aesthetic, which is identifiable as such by the average cultural observer. When you walk into an art space you feel slightly confused and have to deal with what’s in front of you. ‘Contemporary’ is an obstacle to the actual art itself. Theatricality is a way to divert it.”

– Timothy Murray