As a child, when Luke Rothschild was sent to his room for misbehaving, he would collect pots and pans and take them with him to “make sounds.”

As a child, when Luke Rothschild was sent to his room for misbehaving, he would collect pots and pans and take them with him to “make sounds.”

His earliest memories center on him making music, but he was also constantly drawing, forever painting and always creating. This childhood preoccupation with several media proved strangely prophetic.

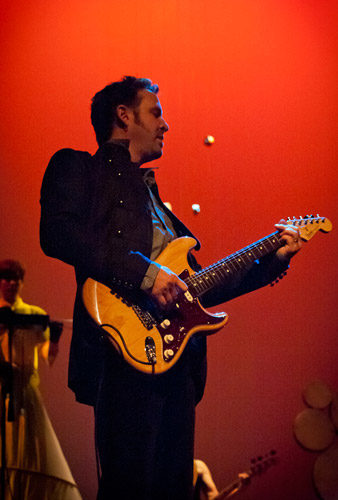

Today, Luke Rothschild is a composer, musician, instrument designer and visual artist, whose work spans a unique stylistic spectrum. He has performed at the Grammys, his giant harps have been installed on buildings designed by architects such as Santiago Calatrava, Frank Gehry, Richard Meier and Frank Lloyd Wright. He has composed several film scores and last year he was named a Sundance Composer Fellow.

This multidisciplinary approach to integrating various media was, he says, nurtured at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied sculpture and sound in addition to painting and photography.

In 2002, he co-founded String Theory Productions, a performance ensemble featuring musicians, dancers and sonic sculptures—probably the only group in the world that provides so many media in one performance. Rothschild designs and constructs the long-string architectural installations at the heart of the String Theory sound and performance.

What is your favorite medium?

I don’t have one. Many art forms and expressive media inspire me. Obviously, music is a sensory experience that develops in a way different to what you experience when looking at a painting… but there is huge inherent power in both.

Why did you choose to work with long-stringed instruments?

I was immediately attracted to their sonic nature and the fact that they were new. Most people had little frame of reference for how they worked. I loved the potential of their vast physical and visual nature. It seemed like the sky was the limit with this tactile, physical and visual way of making music.

You strive to incorporate music and design. Is this easy for you?

Sometimes it’s very challenging, and sometimes it just clicks into place. When there are more logistical parameters in play and more constraints, it can actually help. Knowing what you can’t do tells you what you can do. Creating a new space by adapting an existing space into a sonic and physical musical installation generates a heightened aesthetic and immersive experience.

Your giant harps have been installed on buildings designed by the world’s leading architects. Where did this idea come from?

After experimenting and developing the long-string installation method, it just became clear that architecture was an inherent component. The next step was to find buildings and contexts that would be great fits for this type of installation.

Who is your favorite architect?

Right now it’s Santiago Calatrava.

How do music and architecture work together?

They accentuate each other by contrast. If you take the concept that Goethe put forth that “architecture is frozen music,” then you could say that music is liquid architecture. Another way of looking at it is that music is invisible and ephemeral, whereas buildings are visible and immovable and permanent. In each other’s presence, both are more pronounced by contrast.

Where do you live?

Venice, California.

Where would you like to live?

Venice, California. Barcelona. Manhattan. Vancouver. Chebeague Island, Maine.

What music do you listen to?

Satie, Beethoven, the Pixies, Debussy, Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Chopin, Hendrix, Mingus, and Bartók.

Finish this sentence: “Hello. My name is Luke Rothschild, and I am a…

… human who is an artist.

Text by Ellen Georgiou

Photography by Christa Mae