The Western: The American Genre. We could be heroes. (but why bother?)

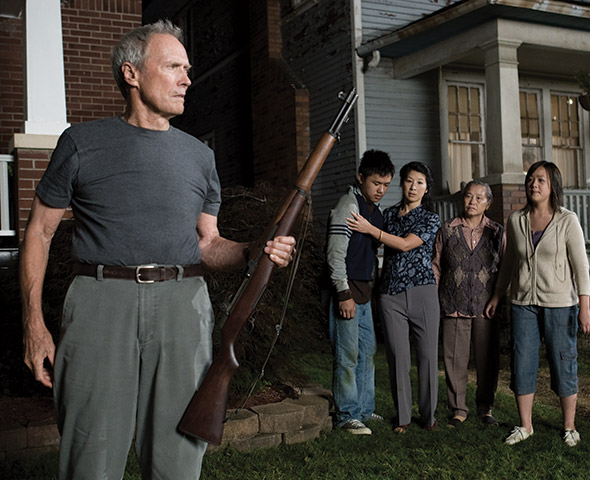

Gran Torino

Text by David N. Meyer

Westerns—once the American myth, America incarnate. Now, hardly relevant. Once it was easy to be a manly man; easy because Westerns told us how. A manly man never expressed emotion, never stopped until he achieved his goal and was never diverted by swarthy outlaws, uppity aboriginals or the unpredictable emotions of women. Violence expressed manhood and getting girls was secondary. Violence made traditional Western heroes hot, and sex made ‘em nervous. That hero paradigm would not survive the ’60s. When many obsolete paradigms came a’tumblin’ down, the Western got seriously revised.

Sergio Leone, a fat little Italian man, pretentious and insecure, had a gift for operatic gestures and subversion. Who’d guess he’d undo the whole deal? The whole sixty years of Western hegemony? After spending half his adulthood making sword and sandal epics (recommended: Colossus of Rhodes), Leone directed a cheapo Western on the mega-cheapo back lots in Spain, an almost shot-for-shot copy of Akira Kurosawa’s goofy Samurai fable, Yojimbo. Fistful of Dollars starred then TV B-Western extra Clint Eastwood and Clint, in his own words was “the first in the history of movies to fire first.” Since the beginning of cinema, strong, silent Americans always waited for the bad guy to go for his piece. Then they demonstrated their moral superiority by being quicker. But what were morals to Clint? Bounty hunters killed for money, and the more corpses piled up, the richer he became. Hear that sound? That’s a key pillar of the traditional Western toppling into the Spanish sand. Leone’s subversion succeeded because Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly became, shockingly, world-wide hits. Leone had a sense of humor, an ironic (back when that word meant something) pop-art visual sensibility, and Ennio Morricone as his soundtrack composer. Together, they proved the most dangerous thesis: that nothing (in the Western) was sacred.

In 1969, old-school macho posturer Sam Peckinpah got serious. Think of his Homeric epic The Wild Bunch as the flaming sword that swept all before it—like the first Ramones album, only bloodier. Peckinpah evoked the spectre of Vietnam, bringing machine guns and early automobiles into the Western. He staged the goriest, most nihilistic gunfights ever seen, orgies of gang violence climaxing with orgasmic fountains of slow-motion blood. The Wild Bunch asserted what traditional Westerns only hinted at: the Western equaled male bonding taken to psychotic levels. Rather than seducing women—or admitting their lust for one another—cowboys preferred to kill. Bunch has more edits than any film ever made. A touchstone of American cinema, Bunch brought the arty self-consciousness of the European New Wave to the shoot-out.

Robert Altman brought hipster nihilism, existential malaise and fightin’ capitalists to the West. His McCabe & Mrs. Miller cast its hero—Warren Beatty as a dim-witted, love-struck wannabe pimp—against a corporation that gobbled up the free-range operators upon which the mythical history of the Western was constructed. Despite its exquisitely painterly visuals—shot by later Spielberg favorite, Vilmos Zsigmond—McCabe seems like what might have actually happened. It’s surreal realism made supposedly realistic Westerns seem like cartoons.

Maybe that’s why there hasn’t been a wholly effective Western in years. We can’t unlearn what we know; there’s no a’goin’ back to them un-self-conscious times. Bearable failures, like Kevin Costner’s Open Range, crash embarrassingly when they strive for sincerity. Has time ever moved so slowly as during Range’s final moments, when Costner attempts to convey his love to Annette Bening? Even she looks desperate to flee.

Ed Harris’ recent adaptation of private dick bestseller Robert B. Parker’s deadpan Western, Appaloosa, proved very “almost.” It’s all post-modern ‘n shit: the characters chat to themselves about themselves, aware of their place in a mythic West their actions help create. Harris—as lead actor and director—gives us a previously unseen, more credible form of shootout. Nobody draws on anybody. They just pull out their hoglegs and stalk toward each other, eyes reduced to slits and fists a’blaze. Too bad that like Westerns of fifty years ago, the story goes to hell when a woman shows up. Harris-the-actor’s bafflement at Renée Zellwegger’s feminine wiles are matched by Harris-the-director’s failure to make her character more than a plot functionary.

The signature American delusions—rugged individualism, necessary wandering, the endless horizon always offering more—came from Westerns. Trust Eastwood, who started the whole damn thing, to put the perfect capper on his arc as a revisionist Western hero. His Gran Torino might be the best Charles Bronson film Charles Bronson never made, but it’s a trad Western in modern guise, with one shockingly revisionist moment that disproves every one of the trad Western myths.

Instead of riding in off the range to fight the corruption of civilization, Eastwood becomes surrounded by corruption because he refuses to move. Instead of the white man being a civilizing force, non-whites regard Eastwood as a grunting beast. Yet Eastwood employs judicious violence and unrelenting moral superiority to inflict his organizing will on urban chaos. Eastwood cherishes the final showdown not like John Wayne, but like a man who grew up on John Wayne. And in the end, and most revisionist of all, Eastwood chooses the ultimate non-violent strategy to win the day.

That sound you hear? That’s John Wayne turning in his grave at 5,000 RPM.

Some revisionist Westerns you might want to see: Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, The Good, The Bad & The Ugly, Once Upon a Time In America, The Wild Bunch, Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Unforgiven