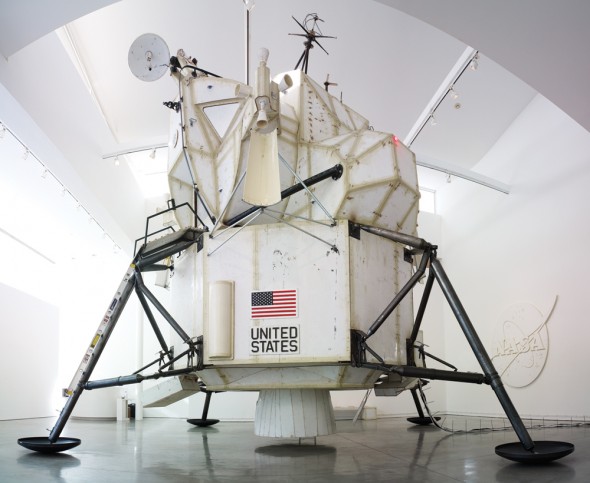

Lunar Excursion Module, 2007

The Sympathetic Illusions of A Modern Day Escape Artist

Tom Sachs is not a genius. By his own admission he is not. For Sachs, a genius is a special kind of innovator, one that pairs a new idea with a new vehicle of expressing it. Charlie Parker was one; Louis Armstrong another. Sachs is quick to admit that he can only do one thing at a time. He can build a hot dog cart-sized McDonalds restaurant, fully equipped with deep fryers, product packaging, uniform, and an emergency button that, when pressed, drops a shotgun with the golden arches branded on the stock into the hands of the employee in need. He even included an interactive video demonstrating the operational procedures of the miniaturized establishment.

If one were to formulate an opinion about Sachs based on this work, he might be seen as an engineer who is sensitive to the plight of the working man. However, this inference would just graze the surface of his intentions.

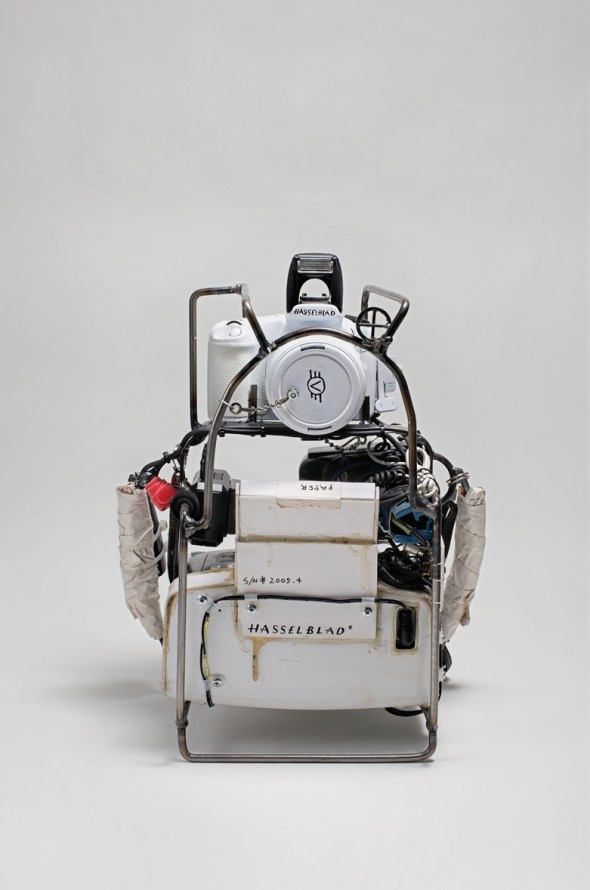

Hasselroid, 2009

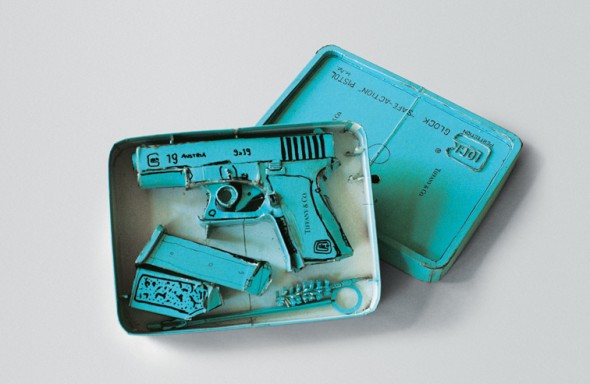

Sachs is a 43-year-old, New York-born and based escape artist. That is, he is an expert at breaking any attempt at labeling, categorizing, or putting a finger on what it is he creates, exactly. While he happens to like the title “21st century American sculptor,” in the end, Sachs makes functional art. More of an aesthetic machinist than a chiseler, his constructions find more of a kinship with applied military science than the classic marble nude. Simply put, he fashions works that work. His homemade Polaroid camera (built from a Canon 20d digital, HP inkjet printer, and an 18 volt Makita cordless drill battery) takes pictures, his waffle bike makes waffles, and his blue cardboard Tiffany and Co. Glock 19 actually fires rounds.

He is the contemporary arts equivalent of Richard Dean Anderson’s MacGyver, and he has been doing it since the second grade. Cameras, his current show at the Aldrich Contemporary Museum of Modern Art, began when he was a young boy with a single magic act to perform. “In art class, when I was eight years old, I made a model of the Nikon (FM2) out of clay and I gave it to my dad because I knew he wanted it. It was like the best I could do because I knew I couldn’t help him buy this camera. So I made it out of clay and it became the very first model I would make for the rest of my life.”

Tiffany Glock Model 19, 1995

Sachs adds, “It was a little bit like sympathetic magic…or like when someone like an Aborigine person in New Guinea will make a model of a refrigerator because they saw that missionaries had refrigerators and food was always coming out of them. They made these models of refrigerators, and they would pray to them and hope that food would come out. And they’d even make runways with the hope that airplanes would land on them and docks with the hope that ships would come visit them. In fact anthropologists did come to look at these make shift docks, and runways, and fridges. So the Aboriginal people, in a way, created their own destiny using art.”

Cameras serves as a perfect introduction to the artist’s uncanny ability to make something out of anything. His building materials range from clay to supermodel Christie Turlington’s trash. The works themselves are exquisite and humble machines, executed with a scientist’s means and precision. This sensibility has become a hallmark for Sachs, whose work is often described as being rooted in Bricolage (the French art of D.I.Y.), as well as the tinkerer art traditions of Jean Tinguely and H.C. Westermann. Sachs’ contemporary evolution of these traditions, set against the current global consumer culture, is what gives such a resonant voice to his work.

Lance’s Tequila Bike for Girls, 2009

In the art world, Sachs is a potent rarity, a genuine “do-gooder.” He founded his studio, Allied Cultural Prosthetics, in 1997 with the intention of “trying to make things that are replacements for things when you’ve lost your culture or your God.”

His portfolio includes the Tom Sachs Space Program, which brought space travel to lucky gallery goers by providing them with a lunar module and a working mission control, and featuring live moon walking demonstrations. In the group show Stages, Sachs helped document the stages of the Tour de France, as well as the stages of cancer development. The show serves as a benefit for the Livestrong Foundation.

Nutsy’s McDonald’s, 2001

For Sachs, what informed his very first work still informs his most recent, and while “sympathetic magic” has given way to “cultural prosthetic,” both terms carry the same intrinsic message. There is no pedestal in the art world of Tom Sachs; his work is as humble as his intent. It is all one playful and interactive attempt to fill in the gaps of our private and public histories—a way of nodding our collective head together. There is no wall of ego; not even a fence. In this place, the artist shares his gifts instead of coveting them. By doing so, Sachs takes on the role of bridge builder rather then monument maker.

– Daniel Dehnhardt