Third World Sound to First World Ears

Akwaaba Music founder Benjamin Lebrave doesn’t feel comfortable with the term “fair trade,” nor with the category known as “world music.”

Yet for the uninitiated, it’s the easiest way to describe the fledgling, unorthodox music label that splits net profits 50/50 with its African music licensees and distributes the songs through its website and iTunes. And unlike most “world music” artists, the 30 some-odd West African musicians, hailing from Mali to Angola, are simply local artists bursting out through Akwaaba and onto a global stage. “What I am doing is not charity,” says Lebrave. “I think it’s funny when people listen to the music and they’re like, ‘wow, this is actually pretty good.’”

The California-based Franco-American was working for a larger digital music distributor, traveling in Europe and DJ-ing in his spare time when a friend turned him on to Ghanian hiplife—a fusion of Latin rhythms, hip hop, R&B and highlife (hiplife’s predecessor).

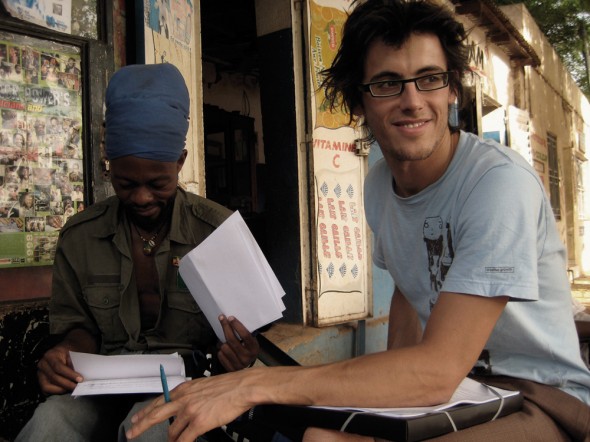

Lebrave was soon captivated by hiplife cassette tapes by artists like VIP, Wutah, Bradez and Praye. Unable to find more of the music on the internet, Lebrave took matters into his own hands, traveling to Ghana himself. Now into the second year of Akwaaba’s inception, the label has released eight albums, starting with the compilation Akwaaba wo Africa, an eclectic mix ranging from traditional acoustic to contemporary dance music fusions.

It’s easy to picture Lebrave as an Indiana Jones-like character, scouring the globe to hunt down rare urban beats with wild abandon, proclaiming, “This belongs on the internet!” Lebrave’s most recent trips found him in Angola, exploring kuduro, a style of dance music developed in the ‘80s when musicians in the region were exposed to American and European electronica.

He explains that kuduro is very modern, accessible and reminiscent of America’s hip hop roots. “People don’t live with much there, so they have one huge subwoofer and they blast the bass from sidewalk bars. It’s the voice of the ghetto—they speak the truth. There’s no bullshit. Sometimes it’s about the bling-bling and all that garbage, but for the most part it’s kind of like hip hop when it started.”

For now, Akwaaba’s future looks bright. From the hiplife of Ghana, to more traditional acoustic sounds coming out of Mali, to the kuduro of Angola, Akwaaba’s catalog is getting thicker and all the more fascinating. At the time of this interview, Lebrave was preparing for a trip to the Congo. As for the future of the label, he says, “I don’t believe in having any specific musical direction…but the unity and importance is more in knowing where the music comes from, how it’s brought to people, and where the concepts come from. So it’s not just urban music anymore.”

– Amity Bacon