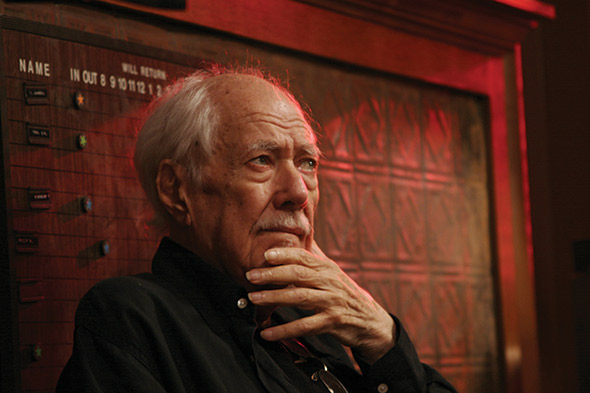

Woody Harrelson and John C. Reilly in Robert Altmans A Prairie Home Companion

The iconic director examines garrison keillor’s historic radio program.

Text by Yon Motskin

If there is such a thing as a quintessential Robert Altman picture, his latest might just be as close it gets. The iconic director is best known for painting cinematic canvases with ensemble casts and overlapping dialogue in films such as M*A*S*H, Nashville, The Player and Short Cuts. Now, with A Prairie Home Companion, a fictional adaptation of the popular radio program of the same name, the 81-year-old director has applied his signature techniques to weave another stylized mosaic filled with quirky characters and sly humor. But what led him to this offbeat adaptation?

“I’ve been a fan of Garrison Keillor for years,” Altman says, referring to the radio host of A Prairie Home Companion. “We share a lawyer. My lawyer came to me and said, ‘Garrison would like very much to talk to you about making a movie.’ I was in Chicago doing the dance film, The Company. We had dinner and talked, and he was at that time interested in doing [an adaptation of his novel] Wobegon Boy. I tossed that around a little bit, but never could get a handle on it – that’s his thing. I said, ‘Why don’t we just do your show?’ And it grew like top seed from there.”

Keillor, who also writes the popular radio variety program, began broadcasting A Prairie Home Companion on Minnesota Public Radio in the late ’60s, around the same time Altman was making the transition from directing television shows like Alfred Hitchcock Presents to features. Millions of listeners tune in weekly to hear Keillor’s deadpan delivery on the satirical show, which includes a rich mixture of elements including phony commercials for Buttermilk Biscuits, tales about the fictional cowboys Dusty and Lefty, and live Americana folk music by Guy’s All-Star Shoe Band.

Though radio man Keillor wrote the fictional screenplay for A Prairie Home Companion, the movie resonates with Altman’s voice loud and clear – more of an impressionistic portrait than any kind of definitive docudrama of the actual show. Taking place over the course of one evening inside the legendary Fitzgerald Theater, the fictional film follows a veteran group of performers off- and onstage during what may be their final recording together. The star-studded cast is led by Keillor playing GK, a thinly-veiled version of himself; Yolanda and Rhonda Johnson (Meryl Streep and Lily Tomlin, respectively) are two of what were four singing sisters; Lindsay Lohan plays the former’s teenage daughter Lola; Maya Rudolph is a spectacularly pregnant stage manager; Kevin Kline is a bumbling gumshoe private eye; and Woody Harrelson and John C. Reilly are the crusty crooning cowboys.

That his new film will draw comparisons to Nashville, his 1975 masterpiece about music, is inevitable. But the new one is different. Shot over 17 days for about $6 million, this film is lighthearted and humorous and moves at a brisk pace with plenty of memorable performances. Streep and Tomlin are especially luminous, while Reilly and Harrelson stand out with a hilarious duet of the off-color tune “Bad Jokes.”

“Garrison created all of the music in the film,” Altman explains, but “everything was done live, no post-recording or pre-recording. All the actors sung all of their own stuff. I don’t think they would have had it any other way. I wouldn’t have hired somebody and have someone else sing for them. [We rehearsed some of] the music for a couple of days, but the rest of it we just shot the way they put on the radio show.”

The Kansas City-born director was delighted to be reunited with his Nashville star Lily Tomlin after many years. “Your communication with actors is, if you work with someone before, you know some of their idiosyncrasies, and you know what you can expect from them and what not to expect from them. It makes a nice shorthand. You don’t have to talk so much.”

He had not, however, worked with Tomlin’s onscreen sister before. “Meryl Streep is the best,” Altman says. “I’ve never had an experience like that. She’s just very, very, very good. It’s like going out and hitting fly balls with Roger whatever-his-name-is. Roger Maris. She’s a pro. She’s so good and she doesn’t make any fuss, whatsoever. She’s a real genius. She doesn’t need a director.”

Like most of Altman’s work, there’s no pressing plot to speak of here. Instead, the film loosely wades through the theme of death – from Lola’s suicide poetry, GK refusing to eulogize an old stagehand, an actual Angel of Death, to the possible end of the show. The notion that life is finite but that the show must go on looms large, especially for Altman himself. Paul Thomas Anderson, the young auteur of Boogie Nights and the Altman-inspired Magnolia, is listed with a special thank-you in the end credits of A Prairie Home Companion. “I am 81-years-old and I’m uninsurable,” Altman says. “So when I do a film, I have to have a standby director to cover the insurance. On Gosford Park I had Stephen Frears. And on this film, P.T. did it.”

Altman was recently honored with a Lifetime Achievement Academy Award but shows no signs of letting up. He just returned from London, where he directed a production of Arthur Miller’s Resurrection Blues at the Old Vic Theater, and is preparing to direct another film that he could not yet discuss. Asked about how he feels this film compares to some of his others, if he can tell it’s special, he dodges the question. “No, no, no, no. I have six children. You wanna know which one I like the best?” He pauses, then says, “I think it’s a strange film… Well, show me another one like it.”