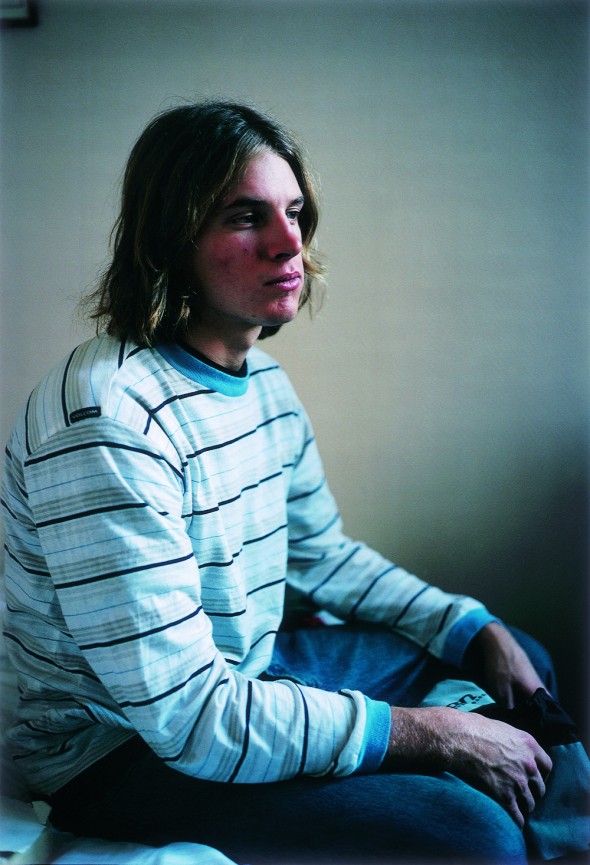

Johan, Gothenber (1999), C-Print, 14 x 11 inches.

On the hustle behind the lens

SOMA: Photographers Steven Shore and William Eggle-ston have said that they consider themselves modern day anthropologists. If you had to give yourself a title, what would you prefer? Artist… photographer… anthropologist…

Ari Marcopoulos: I am a Muthafuckin Hustler!

And so it goes—Ari “Muthafuckin Hustler” Marcopoulos.

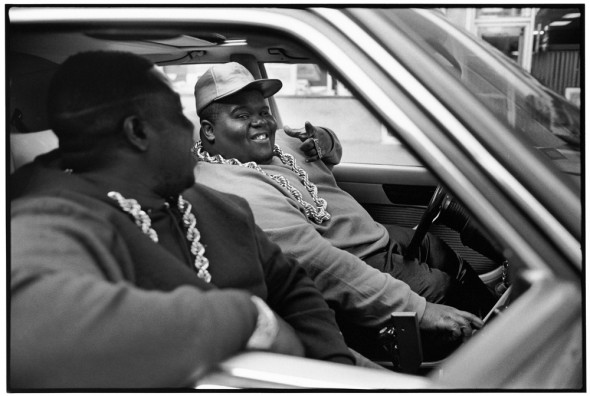

It’s a fitting description for a man who has been working behind the lens for over three decades and is considered one of the virtuosos of contemporary photography. One could say this particular type of hustle has been with the self-taught photographer since he moved from Holland to New York City, where he worked as a printer for Andy Warhol and studio assistant to Irving Penn when he was 23-years-old. There he began shooting portraits of various individuals such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Mapplethorpe and even the rap group the Fat Boys. The latter shoot provided a stepping-stone to the blossoming ’80s hip-hop scene, where he bounced around in the background most notably with the Beastie Boys during their Paul’s Boutique and Check Your Head days. The hustle has since led him to document skateboarders half his age under the Brooklyn Bridge in the ’90s, and even to the Alps with snowboarder Terje Haakonsen where he would eventually learn how to navigate a cliff (and occasional avalanche) after getting dropped off by helicopters on snow capped mountains for the next six years.

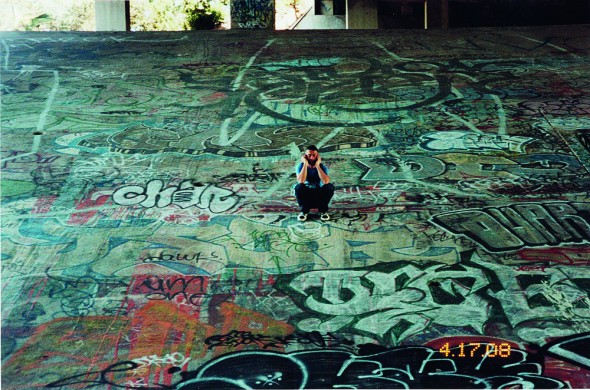

Dictation (2007), C-Print, 11 x 14 inches.

Mainstream audiences have finally caught up with photo-graphers who are trying to capture the “decisive moment” with single-lens reflex cameras and natural light. And while this aesthetic might shift in the years to come, one can be sure that an honest intimacy will continue to follow Marcopoulos whether he’s following his most recent subjects (his teenage kids) lounging around the house, or showcasing his work at his first mid-career survey at the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Marcopoulos answered a few questions from L’Aquila, Italy, via email, where he was surveying the damage of the recent April 6, 2009 earthquake. When asked what brought him there and what he is looking for, he writes, “Coincidence… I’m not looking for anything.”

Fat Boys I, (1986), Gelatin Silver Print, 20 x 24 inches.

What is a mid-career survey anyway? It sounds ominous, like you only have “X” amount of time left, you know? What did you want viewers to take away from your own history when putting this collection together?

The exhibition was put together by Stephanie Cannizzo, a curator at the Berkeley Art Museum, so to a large degree, it reflects her point of view. And no, it does not feel ominous, it spans 30 years of work so, if that is the middle. I still have 30 years to go as far as my career is concerned.

You have said that you kind of let the work find you, but why do you believe the skateboarder culture, for example, came into your life?

My interests bring the subjects to me. I like skaters because they live on the edge and they have a cool mentality when it comes to hanging out with kids from different ages; backgrounds. Skating brings them together.

Can you give an example of when you might have put yourself in harms way to get a photo? When you are in precarious situations, like your years spent with the snowboarders. Does your camera act as a shield?

My camera never functions as a shield. I have never photographed in a war-type situation. So, the most danger I have been in was probably in the mountains, standing on a ridge when a huge avalanche ripped out right underneath me and, there, the camera did not help much. Common sense was the protector there, although common sense also wondered why I was jumping off a helicopter in Alaska’s Chugach Mountains.

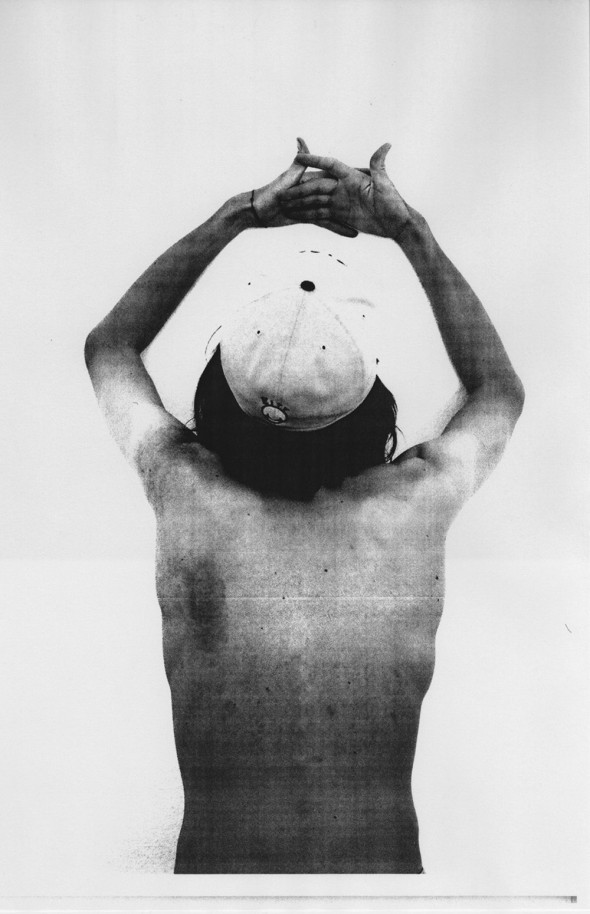

Angel, (2008), Xerox Print, 53 x 38 inches.

Do you consider yourself a storyteller in some regard?

It’s not so much being a storyteller. I’m an observer/participant, I think. The story might follow, but more in the head of the viewer then mine. The viewer is left to create the story. I want people to come away with recognition or memory of their own parallel experiences.

How important are accidents in your approach? Would you say that working behind the lens was initially accidental?

Accidents are crucial in more ways than one. But being behind the lens was a deliberate choice.

You have noted that you usually try not to think too much about composition or formal guides. So it begs the question, when do you know that you have captured a moment?

It all depends. In a way, it is not a moment I am looking for, unless it is an action photo, which I rarely do these days. So, often I don’t know really, it is just a feeling. You win some you lose some.

After all of your years behind the camera… all the assignments and all of the history… what do you still find mysterious about the act of taking photographs?

The fact that a simple photograph can be a beautiful thing…

– Patrick Knowles