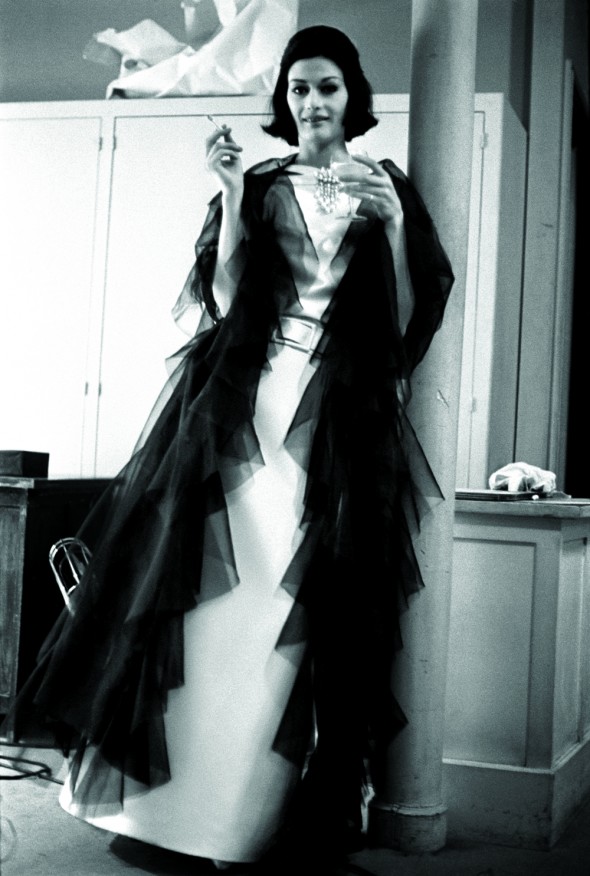

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Behind the scenes at YSL’s first show

It’s Paris 1962, Yves Saint Laurent has just started his own business, only five years after taking the reins from Christian Dior at age 21. It’s easy to identify this as the last great period of haute couture, spurring the subsequent rise of prêt-a-porte. It’s a time idolized in fashion, when clients and press were a limited society and before the advent of modern celebrity. And for many, it was a time when the entire history of fashion was only just reaching its modern form.

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

The evolution of fashion had many moments of crystallization during the mid-20th Century. However, there’s no single garment or collection that speaks for all of fashion. But for Paris in the early ’60s, these breakthroughs were ongoing and symbolic with nearly any branded good having a traceable relationship to this very period.

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Esquire Magazine sent Jerry Schatzberg to shoot the fashion collections in Paris in 1962. By then, he was looking beyond the traditional form of fashion photography, where editors secured garments and then sent them to studios for late night photo sessions. Instead, Schatzberg pioneered street photography, capturing the so-called decisive moments. In the midst of the mundane and the regular, Schatzberg wanted to focus on an undeniable sensation of something in the air—the prospect of omnipresent beauty. In the days of film photography, Schatzberg was spinning conventions, making the guests and atmosphere his unsuspecting subjects while shifting fashion into the subtext. But he also tried to document the traditional methods, formally photographing Norma Parkinson and Helmut Newton as they worked.

Growing up in Manhattan, Schatzberg had simply wanted to escape the family business (ironically selling camera equipment). So he’d started assisting photographers like Bill Helburn before going on to shoot for Vogue, McCalls, Town and Country, and the like. Later, he went on to run legendary nightclubs in New York like Ondine and Salvation.

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Schatzberg would go on to direct a series of films like The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979), The Panic in Needle Park (1971), and Honeysuckle Rose (1980). Sitting for an interview at an empty restaurant in the West Village, he admits critics had faulted his first film, Portrait of a Downfall Child (1970) as markedly not-Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-up. Today, it’s celebrated for the same reason.

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Juliana Cairone, stylist and owner of Rare Vintage in Manhattan, deals regularly with original garments by Saint Laurent, Dior, and Marc Bohan. She explains some of the fascination: “Fashion is about dreaming, I don’t think fashion exists without dreams and ideas. Otherwise we would all wear a uniform and there would be no interest. Jerry’s images, they are of such a different world. They are so beautiful, I can’t imagine any woman who would not want to try to look like that—get a bit of that feeling.”

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Schatzberg mixed fashion and street photography in a way that had not previously been seen. And in this series, it’s simply a relevant perspective during a significant time. Some might say that film photography, in contrast to digital image capture, required money, technique and attention to every frame. Others would say perspective, time and technique sometimes just meet by coincidence, creating art. Regardless, Schatzberg’s images from Paris 1962 are probably best left to the dreamers.

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

Photography by Jerry Schatzberg

– Michael Cohen

Jerry Schatzberg’s work can be revisited in a recent release from the archives Paris 1962 Schatzberg (Empire).