There was an interesting moment a few years ago at the 2008 Slamdance Film Festival. David Lowery’s short film, A Catalog of Anticipations, had just screened, and the director stood at the head of a dark room for a post-screening Q&A session. The questions were timid at first, as if the audience had not expected the opportunity to direct questions towards Lowery, the film’s writer, director, and editor. But it soon became clear that the awkwardly probing questions were the result of an audience that knew almost nothing about Lowery’s filmography. Admittedly, David Lowery’s previous work as a director was relatively limited and obscure. Prior to Catalog, he had only written and directed a couple of experimental shorts, an essay film, and Lullaby, a feature length film made by a 19-year old Lowery that now rests in his own private collection. Eventually, the emcee himself asked Lowery if A Catalog of Anticipations was typical of the kind of work that Lowery was interested in, and if he had any similar projects.

“Tonally, this is like everything else I’ve ever made,” Lowery told the room, a compelling response, considering that Catalog is arguably Lowery’s most experimental work, and the only one to break the boundary of realism: it is a short film consisting entirely of still photos about a girl who finds and collects faerie creatures in matchboxes. “Everything I’ve made feels the same way as this.”

“There are visual parallels amongst everything I do,” he explains, almost five years later. “Corrugated textures, old wood, the same colors – but beyond that it doesn’t take much digging on my part to realize that I’m plumbing the same themes from one picture to the next. I think all of my films feel of a piece with each other, and the more I talk about the new one, the more I realize that those ties are only growing stronger.”

These days, Lowery is making films on an entirely different scale. His latest feature length film, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, debuted at Sundance in January. IFC acquired rights to the film just days after its debut, and the film is slated for a mid-August theatrical release. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints is a stark contrast from Lowery’s earlier art house films. Though it is a low-budget film compared to others seeing theatric releases, it is Lowery’s first film to exceed a five-figure budget. St. Nick, Lowery’s first feature length film, was made for just $12,000. Saints is also the first film of Lowery’s with a significant mainstream appeal. Lowery was able to land Oscar nominees Casey Affleck and Rooney Mara in leading roles, and secured Ben Foster and Keith Carradine as supporting actors. The film is a romance-driven drama that tells the story of separated outlaw lovers. But even through its mainstream appeal, Saints is rife with intense emotions.

“I don’t think I can make a film that’s not personal,” Lowery says. “I hate to be so solipsistic about it, but that’s the only way I can approach a project. I’ll lose interest if I don’t have something personal at stake. I’ll stop caring.”

Ain’t Them Bodies Saints would not exist the way it does today without Pioneer, Lowery’s preceding short film. Pioneer was Lowery’s stepping stone from limited art house releases to the summer theatrical release of Saints. It featured singer-songwriter Will Oldham acting opposite of five-year old Myles Brooks. It was a noticeable benchmark of Lowery’s confidence as a director and writer coming to fruition. The 15-minute short was the first of Lowery’s films to feature prominent dialogue. In fact, Pioneer had more dialogue in its 15 minutes than St. Nick did in its 86-minute entirety. The film came out of the 2011 festival circuit with a slew of awards, which gave Lowery the momentum to move onto a bigger project and attract an acclaimed cast for Saints. In fact, when sending out the script for Ain’t Them Bodies Saints during casting, Lowery included a copy of Pioneer. This allowed him to showcase his growth from films like St. Nick and The Outlaw Son, which featured virtually no dialogue, to a film consisting entirely of dialogue that was able to rise to critical acclaim without ever leaving the space of a single room.

“Pioneer goes in a completely different direction and is bound by an opposite sort of rigor,” says Lowery. “I didn’t conscientiously set out to do something different or contrary to my previous work, and I think thematically it’s very much a continuation of what I started with St. Nick. But practically speaking, I was certainly excited to try something new, to focus on performance and really dig in and work with actors on something very specific.”

Though Lowery’s career has advanced far beyond the unfamiliarity of the 2008 Slamdance screening, he remains relatively obscure (he doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page). But as he moves closer to renown, people will undoubtedly begin to search for his past works. His true filmography, though, is elusive. Some of his short pieces appear, in samples or in entirety, on his website. St Nick is nowhere to be found. Lowery, for a time, considered a DVD release of the feature-length film. But as a director who is cautious of the legacy of his formative works, he eventually decided against it, settling instead for a limited, one-week only streaming.

“I think I was worried specifically about seeing something that was so personal being reduced to something disposable,” Lowery says of St. Nick. “But generally speaking, I want my work to be available. I want people to be able to see it.”

And as Lowery’s fame begins to mount, so, too, does the notoriety of Lullaby, his first filmmaking effort that will never again be seen by the public.

“Lullaby was my first attempt at really making a movie,” he explains. “I was 18 when I wrote, 19 when we made it. It was an amazing learning experience, but I hope people trust me when I say that it’s not worth being curious about. The best thing that came out of that experience was meeting one of my best friends, James M. Johnston, on it, and the partnership I’ve had with him on every film I’ve made since.”

Text by Cale Finta

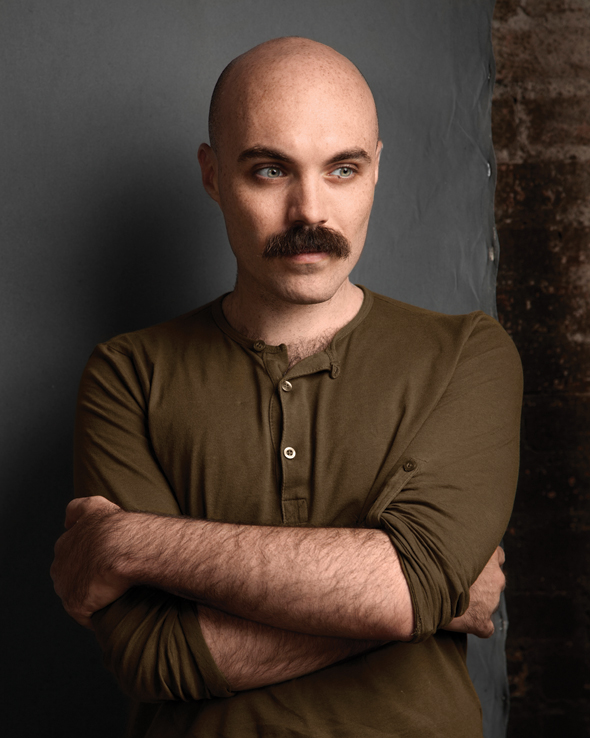

Photography by Stanton Stephens