Setting the DJ Scene Ablaze

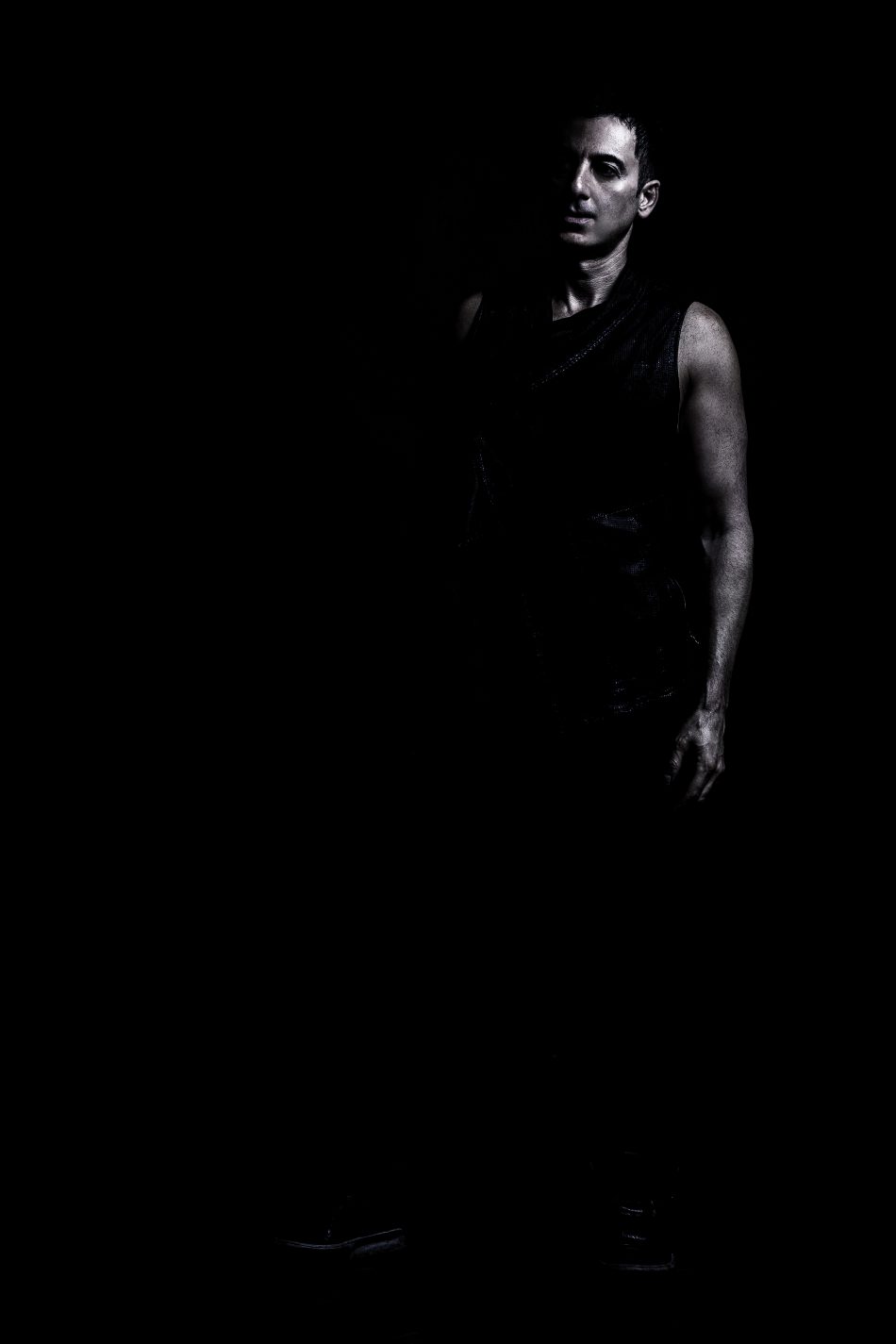

Before he was Dubfire, he was Ali Shirazinia: a young Iranian boy, newly immigrated to America, constantly on the outside looking in. Foreign to his peers and an average student, Ali’s chances of fitting in were slim to none, but fitting in was never what Ali was destined for. His offbeat interests were allowed to grow and develop organically without the stakes of losing popularity points, which is perhaps what attracted him to the niche genre of electronica music.

As he started to become a DJ, Ali entered the scene on the cusp of its popularity in the United States and was unknowingly about to be swept up in that wave. His unpopularity came to an end as his musical contributions became part of the catalyst that launched electronic music into America’s mainstream. Ali and fellow DJ, Sharam Tayebi, became the two halves of the DJ duo “Deep Dish.” They went on to win a Grammy for their hit remix of Dido’s “Thank You” and 4 years later, were nominated for their single “Say Hello.” While they were regarded as arguably one of the best electronica acts of their time, the DJ duo had a known volatile relationship that wasn’t built to last. After a decade, their partnership crumbled, leaving Ali to pick up the pieces of who he was and fit them back together in the form of a solo act. Thus, Dubfire was born.

Ali, now permanently known as Dubfire, set the DJ scene ablaze with his single “Ribcage,” which was one of the major career turning points that defined him as a solo artist. Since then, Dubfire is featured as the subject of the documentary “Above Ground Level,” and he’s about to release his new album “Dust Devil.” While he felt wildly out of control of his circumstances as a child, Dubfire uses his techno beats like a hypnotic, steady heartbeat to place himself back in a state of consistency and power. As he travels the world playing his sets, Dubfire calls the shots, sending out different waves of emotions over his audiences like movements in a symphony. With his music, Dubfire ignites that same spark that once inspired him as a child, and now watches it spread through the crowds like wildfire.

When you first started out, you incorporated jazz and funk influences into your music. Did you start off playing these other genres?

Yeah, when I was really young, I was always into alternative and left field music. When I actually started to play out at places like house parties, I recall playing a lot of new wave and industrial music because that was what I was really into at the time. I went through different stages. I remember at one stage, I had a mohawk. At another stage, I had the new romantic look, and waves look. It all depended on the music, who I was feeling musically, and which kind of music spoke to me. And I think getting into the more electronic body music or industrial music led me to discover bands like Kraftwerk, and other electronic bands of that era. For as much as I was interested in Washington DC, which had a world-renowned punk rock scene, I also had a deep interest in what was happening on the other side of the world in Europe with electronic music. So for me, the two scenes always ran parallel to one another and I was following all the artists in both camps, and eventually, everything kind of merged for me.

You had a volatile relationship with your partner, Sharam. What were the components of that relationship that worked creatively?

For us, all the great things that would happen, all the great music that we made, the majority of our career was made under duress. It was a lot of arguments, a lot of fights that sometimes got physical. It was just really heated. It was the difference of opinion that we had towards everything: towards business, towards the approach in the studio, towards the sound we wanted to go for, certain rhythms, drum programming, bass lines – It was hilarious, we fought over everything. And it was that tug of war that ultimately created the balance, and sometimes imbalance, of Deep Dish. So for whatever reason, it worked for quite a number of years, and eventually it just reached the end of that cycle and we had to go our separate ways.

Ribcage was an extreme departure from anything you did with “Deep Dish” and seemed to be a wholly concentrated dose of you. What state of mind were you in when you created Ribcage?

I had a range of emotions going on at the time I made the track. I had just come out of Deep Dish, so I was very unsure about my ability as a single artist, but I was really passionate about the music I was feeling at that time, which wasn’t what Sharam was doing. I knew instinctively the direction I wanted to go in, even if I didn’t know if I would be successful within that genre. Sharam and I were basically bringing house and techno together in a new way, so I represented techno, Sharam represented house. I was going back and reconnecting with those roots, and going out to see some of the DJs in techno. That gave me the motivation. We didn’t really swim in those circles as Deep Dish, because we really became like a commercial phenomenon. We started playing different events, which is why I went back to the events I had always wanted to play and scenes I wanted be part of. I had ideas that could push the genre in a new direction. So then it became a matter of getting together with my amazing engineer, Matt Nordstrom, and figuring out a way to do that: To translate the ideas that I had whenever I came home from one of those trips and to do something audible and Ribcage was a result of that.

Do you ever hear sounds out in the open in the real world and try to replicate them digitally?

Sure, all the time. One example is I’m well known for the white noise explosions or crashes in my music. That all came about when this club or festival had these C02 cannons, and whenever that would go off, I would notice that it would create this new energy. I wanted to capture that moment and feeling within the music. So that’s what I worked on in the studio and it became synonymous with my sound. I’m constantly hearing sounds, whether I’m on a train, or construction site, or a sound in nature that can give me a spark of an idea that I can do in the studio. A lot of what we do as DJs and producers is we want to connect emotionally to people and trigger memories. And while I’m triggering memories and emotions in others, it’s happening to me right there in the DJ booth as well.

It’s interesting that your documentary puts an emphasis on food, because electronica icon, Jean-Michel Jarre once compared creating electronica music to cooking and combining ingredients.

Oh yeah, I’ve been using that analogy for years as well. It’s very, very accurate. I feel a lot of similarities and forged relationships with a lot of chefs because of our shared passion for what we both do. If you just look at a DJ set, then look at what chefs do as a metaphor for that, our tracks, their ingredients, and how they put their ingredients together and how we program our music ultimately has a direct effect on what we sound like, and what they end up putting on a plate. Putting together those ingredients in a very specific way, it’s what they do to those ingredients that reflects the unique sense of their craft. With music performance and DJing, it’s how we take those elements and how we frame it that tells our individual, unique story. So there’s endless similarities.

Would you eventually want to use your platform for a specific cause?

Yeah, I actually have a very soft spot for the deaf and deaf schools. I’ve had extensive conversations with companies like SubPac with the wearable subwoofer, which pushes the bass frequencies through your body. [When] you have it connected to an audio source, you feel the music. You could be sitting at home, but you’ll feel music like you’re in the middle of a massive festival or club with a huge sound system. So often times I’ll see deaf kids or adults at my gigs and they’ve got their head in the speaker and they’re trying to really feel the music. I don’t know what I’d do without my hearing. Hearing is a big component for what we all do as musicians. My heart kind of sinks whenever I see someone who’s deaf, so I would want to do something for deaf people and I’m kind of known for my bass, so it could be a good union.

What’s on the bucket list for Dubfire?

With this [latest] compilation, it’s kind of capping the first ten years of my solo career, and in many ways, I’m trying to push myself and, of course my engineer in the studio, to come up with new tricks: To not rely on the same process that we’ve always had with the music making. Sometimes you can get comfortable if you become well known for a certain sound. You tend to repeat yourself, whether if that’s what you’re trying to do or not, it ends up creeping into the creative process. So sometimes we may work on something and I’ll do it one way, and once we have that version, we’ll take a completely different approach. So I’m really trying to take myself out of my comfort zone.

Text by Zee Chang