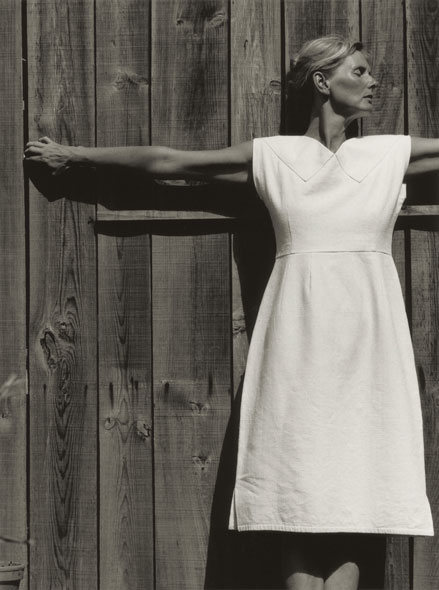

Avoiding the label of designer, this photographer transforms photographic

qualities into dimensional garments that capture more than just attention

Text by Michael Cohen

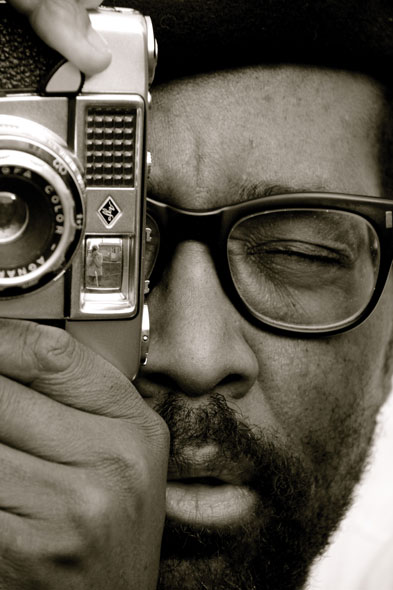

Photography by Koto Bolofo

Photographer Koto Bolofo is prized for his ability to present honest beauty. His signature is to forsake gimmickry, respecting subjects and composition. He works in film rather than digital format, giving the final product more depth, while placing a premium on every image captured. In practice, Bolofo thinks before he shoots, a sensibility too often lost in today’s technology.

Bolofo sees the world though a pinhole of color and shape. He both fulfills and exists beyond the archetype of photographer, one who cherishes light and texture, while scoffing at art directors who request cliché imagery to fulfill a marketing narrative. Deeper than the ethical or aesthetic abstraction, truth is evident, as for any artist, through his body of work.

Describing his recent womenswear collection for Anthropologie, Bolofo insists he is not a clothing designer. Rather, he sees the garments as a manifestation of his photography, explicitly saying,

“The idea was that if you wore the garments, you wore a dream, or you were wearing my photographs. What I do in photography lays flat on a piece of paper. [In this collection] the photograph has come alive.”

Maybe Bolofo is wise to think in this manner. He understands that the world, his clients, his friends and collaborators need to see him as photographer. With this title, he is known and trusted by powerful people and companies. This is evident in partnerships such as his one with Hermès, in which Bolofo’s 11-volume publication La Maison chronicles the secretive inner workings and workshops of the legendary fashion house. But as fashion designer, he is a neophyte, an aesthetician operating outside his comfort zone. Designer is a title that leaves a world-class photographer susceptible to criticism.

This is certainly the initial response Bolofo received when presenting his garment prototypes. Bolofo says, “It just felt like [they were thinking] what’s he trying to do? I was trying to show them photography. They looked at me, like I was trying to be a designer and trying to be a photographer at the same time. I tried to shop around in Europe. No one wanted to do anything. [The garments] remained in my archive boxes.”

In retrospect, Bolofo insists he is not a fashion designer, lacking the intent to sell clothes, and explains that the collection is directly tied to his work as a photographer: “When I started in the early ’80s, the textures had a certain quality, when you click the camera, you felt the texture. There’s something vibrating in your eyes to say ‘I like that’, because the texture was good, the materials were so alive, they felt so rich. As time went on, when you looked close, something had changed with the clothes visually, the industry was cutting corners. The texture doesn’t have the same body. Sometimes you have to distress the garment, you know, bash it, to build the textures.”

Concurrently, Bolofo was collecting vintage linens, enamored with their texture. He explains the experience as, “The sheet, when you touched it, had a real fantastic sensation.” Soon, he’d unwittingly become a hoarder. “ I thought to myself, why have I got hundreds of sheets? What am I going to do with them?” The simple answer was to turn those linens into garments. Bolofo continues, “People have slept in these sheets. They contain unknown dreams.”

Bolofo’s career has not lacked for highlights, he’s photographed books with Venus Williams and Lord Snowdon; a documentary, The Land is White, the Seed is Black, about his family’s story as South African refugees returning from England; and ads for the likes of Louis Vuitton and Dom Pérignon.

Unexpectedly, shooting catalogs for Anthropologie brought the garment prototypes out from his archive boxes. He recounts, “Working with these people was very comfortable. They booked me again… same feeling, the type of girl and casting that I like.”

An email arrived inquiring about projects beyond photography. Bolofo began thinking about his garment prototypes but resisted the urge to present the work, remembering earlier rejections. When the email arrived again, he couldn’t ignore it.

He says, “I’m going to go back in the cupboard and pull those prototypes out. I thought, I really love those prototypes and love the material. There’s a sense of deep, enduring love in this. I took four garments and four photographs

and wrapped it up with lavender.”

Sending it off and expecting the garments soon to be returned, Bolofo was instead asked to visit Anthropologie’s Philadelphia headquarters to develop the concept into a collection. Bolofo says, “You always use the expression, ‘they are thinking out of the box’. Here it was no box at all. It was a dream

that really came true.”

When it came time to review the final collection, Bolofo expected the garments to fall short of his original hope. He says, “I thought I’d hear, ‘We couldn’t get this right and we couldn’t quite fabricate this’. I’ll be really happy that they did try at least, they did take me down this road.” But, he exclaims, “I couldn’t tell the difference between my prototypes and theirs.

They really got it right.”

In a series of capsule collaborations with Anthropologie, entitled Made in Kind, Koto Bolofo’s garments sit alongside notable designers such as Karen Walker, John Patrick, Samantha Pleet and Gregory Parkinson. His new book Dreams accompanies the collaboration, offering a visual story of the collection. So maybe Koto Bolofo is not a fashion designer. Perhaps he dreamt to become a designer, then forgot the dream. But someone found his sheets and remembered this dream. And somewhere in that abstraction, his work says Koto Bolofo can be both designer and photographer.