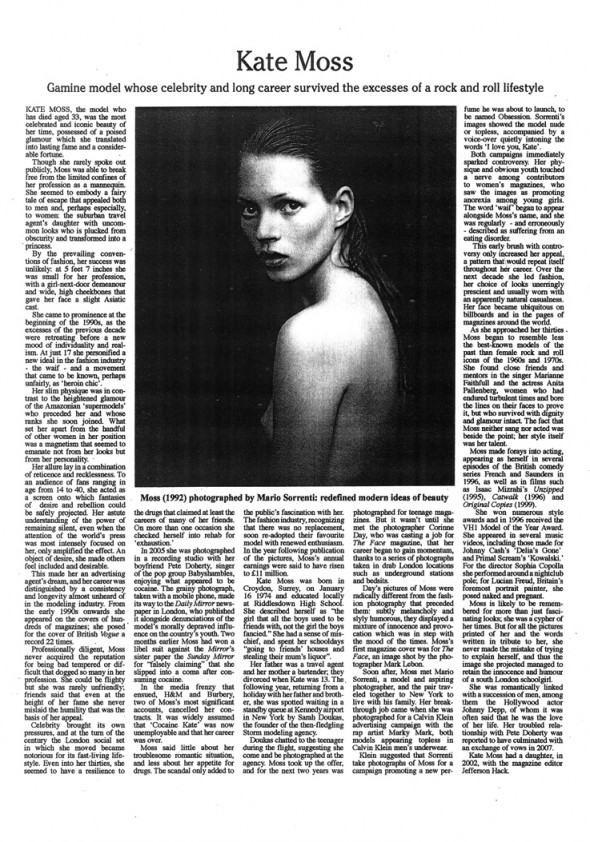

Untitled (Kate), 2007; C-print 52.75 x 37 inches

Adam McEwen: Burning Bridges to the Mundane

Were there a single thread interwoven through his past and current work, Adam McEwen would have no idea what it would look like. “I’m just trying to make the thread visible,” he says. “I don’t know what it is, but I know for me, an obituary of Kate Moss is the same thing as an air conditioner made of graphite. There is a part of me that doesn’t really want to put into words what that thread is, but it always starts from the same place. It’s the same thread that ties together a credit card made of graphite, a photograph of a Jumbo 747 jet or hardware signs that read, ‘Sorry, We’re Dead’ or ‘Sorry, We’re Sorry.’”

Following the connections between the installations, sculptures, paintings and photographs of 43-year-old Adam McEwen is a bit like making sense of air traffic control flight paths during the holiday season. It’s simply difficult to know where to begin. One might be standing under a set of 6’ long light tubes made of graphite in a warehouse in New York’s Chelsea district, and then realize that the work hanging from above them was created by the same artist who posed as the controversial British hero, Arthur “Bomber” Harris, in a black and white photograph next to large dirty gum-filled canvases named after destroyed German cities. Essentially, McEwen is the kind of artist who keeps critics guessing, fans curious and journalists trying their best to unravel his intentions.

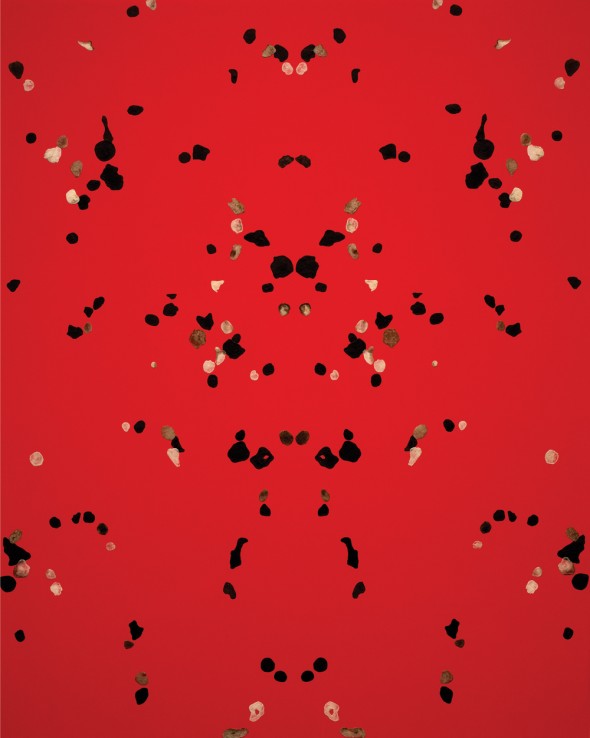

New York, New York, 2008; Acrylic, chewing gum, canvas 65 x 52 inches

It should be mentioned that there is a certain democratic feel to McEwen’s work and that this London-born and New York-based artist has a way of rethinking familiar day-to-day cornerstones. Most people are familiar with city sidewalks littered with discarded gum; text message abbreviations sent while en route somewhere in a cab or on a mass transit system; and how the death of a celebrity can trump chit-chat formalities between strangers. However, it is these very same seemingly mundane mediums toward which McEwen gravitates. In doing so, he is able to invite viewers into a world we already know — and turn it completely upside down.

Speaking over the phone during a brief vacation in the Caribbean, McEwen is quick to note that he doesn’t exactly know what he is searching for with his work. Yet he also doesn’t have any trouble talking about why he continues to look towards the streets for inspiration. “I spend a lot of time walking around the streets in New York and I get a kick from the combination of grime and beautiful architecture of the city. It’s brutal but positive at the same time,” he says. “I really like all of the signs everywhere in the doors and windows that say things like, ‘Sorry We’re Closed.’ It took a place like New York to find a joy in that. Trying to deal with the information overload allows me to find things to work with. I suppose I feel that while I’m there I might as well mess with it.”

As a young boy, McEwen fondly remembers staring at an Ed Ruscha gunpowder painting (with the words “Cheese Chinese” drawn over a solid backdrop) in his living room growing up in London. Ruscha happened to have been friends with his father (who was also an artist) in the early ’70s. Whether or not the time he spent looking at that particular canvas led McEwen to pursue mixing words and art might be questionable, it is a fitting image for what was to follow—as he is often referred to as a student of Michael Asher, Warhol and Ruscha.

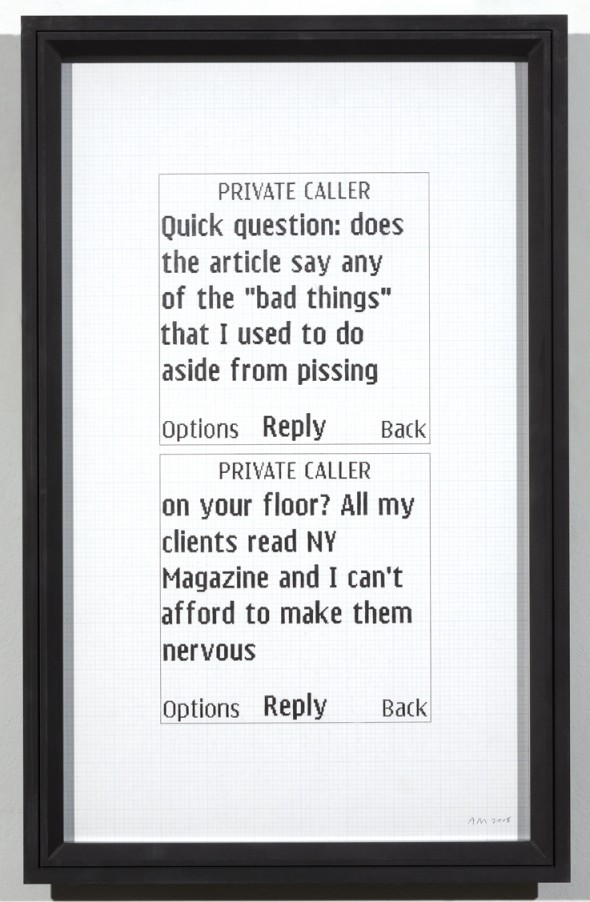

Untitled Text Message (Private Caller), 2008; Pencil on graph paper, graphite frame 17 x 10 inches (image) 18.25 x 11.5 inches (frame)

Soon after, he graduated with a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Oxford in 1987. He even held down a brief stint working at the Daily Telegraph writing obituaries for the deceased— an assignment he was to later revisit in ’04, when he featured obituaries for obviously still living celebrities in his show “History Is a Perpetual Virgin Endlessly and Repeatedly Deflowered by Successive Generations of Fucking Liars.” The work is still in progress five years later, and has featured the likes of Bill Clinton, Jeff Koons, Nicole Kidman and will soon include the author Bret Easton Ellis among others.

Regarding the use of text in his art, McEwen says, “I find that words just kind of circle around and come back to me a lot. I never get bored of using words visually. On the other hand, I wrote an obituary to Marilyn Chambers because the first pornographic film I saw was Behind the Green Door, so I suppose my work is also a homage to the things I grew up with.”

This personal sentiment, while not apparent on the surface, was also what led McEwen to relearn what he was taught in history class regarding wwii in his “Gum Paintings.” “I remember when I was 12, I was taught that Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris was a cool guy. He wasn’t exactly a hero, but he, ‘just did what he had to do.’ Twenty-five or 30 years later, I learned how intense and insane his campaign was to flatten every German city. The ‘Gum Paintings’ are about the difference of me being 12 or 13 years old and being 40. I suppose that it is about how people think about history and how it is like fiction. In that sense, I suppose that at the end of the day, my work is still my story, but maybe I can take someone there too.”

Switch and Bait,2009; Graphite, light fixtures Diminsions variable

One could argue that this historical thread has led McEwen to his most recent work “Switch and Bait.” Viewers enter a dilapidated space, where rows of “fluorescent” lights made of graphite hang above their heads. The room next door is empty save for a podium displaying an American Express credit card with McEwen’s name on it. The extensive sculpture seems to address minimalism and repetition, but one can’t shake the ghostly reference to factory work and the assembly line context that dominate industrial 9 to 5 jobs of the city. McEwen says, “The sculpture refers to that efficiency and cleanliness of work, but the graphite is dirty.” He pauses and adds, “The back story to minimalism is not one of a pure and holy aura. There is a more human and dirty and flawed back story and I thought the graphite could get to that.”

With over 50 exhibitions to his credit since 2001, it is safe to assume that McEwen will continue to weave through genres in the art world for years to come. When asked if he felt that his varied interests were beginning to take the shape of a personal statement he takes a long pause and says, “I don’t think that you have to know what you are doing. I don’t even know what I am asking in general. It’s not a manifesto. I just don’t want it to be exclusive. I want it to be somewhat human and genuine.”

– Patrick Knowles

All images courtesy of the artist and Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York, NY.