Text by Scott Indrisek

We are surrounded by webs of information and surveillance – databases, crime cameras, entire hidden matrixes of observation and recording. While some may choose to loudly protest the status quo as an invasion of civil liberties, others are taking subtler approaches, tweaking and provoking the system in a way that exposes its quirks and inadequacies.

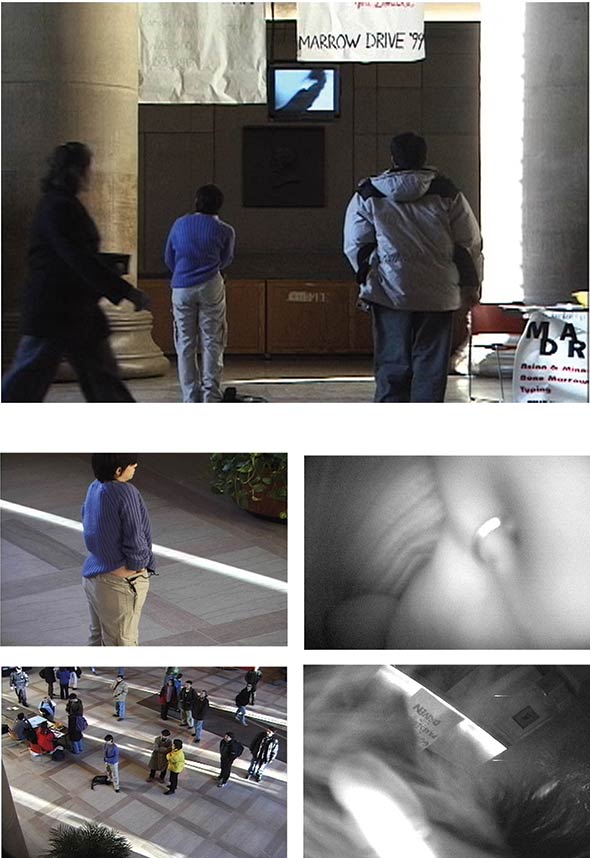

Jill Magid is a New York-based artist whose best work combines an eye for social research with a talent for intelligent provocation. “I treat systems like lovers,” she says. “I treat the system like a body in relation to my body.” As an MIT graduate student in Visual Studies, she electronically hijacked the institute’s main informational monitor in real-time by feeding it footage from a small handheld wireless camera. “When I walked in, I stepped into the middle of the lobby at 12 o’clock and turned the TV to me,” Magid explains. Wearing a baggy sweater, she proceeded to move the spy cam beneath her clothes, projecting a virtual map of her body onto the co-opted television. “One by one, probably 100 people collected around the space. Some people figured it out, many didn’t. The image that you see stretches my body slightly. Since it’s infrared your skin gets glowing white, and it makes the body a kind of landscape. The best compliment I ever got was from one person who said they’d never be able to see the monitor itself the same way. For them, the monitor would always be a different source of information. For me, if you can change the meaning of something like that, it’s really powerful.”

Magid’s fascination with surveillance technology began, oddly enough, with a kiss. After early architectural projects that attempted to envision “a bubble” within the chaos of the modern city, she began thinking smaller. “The Kissmask” links two women by their faces through a collapsible tube equipped with a microphone and videotaped to capture the sounds and atmosphere created during that moment of physical intimacy. “I wanted to see what the space looked like, so I got into spyware because it happened to fit into spaces I couldn’t otherwise be. My introduction to the hardware was simply for the purpose of being able to see into intimate spaces that I couldn’t otherwise see. It didn’t start as surveillance – it started with observation.”

After being accepted to a two-year program at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, she shifted her focus to an investigation of street surveillance cameras. “I wanted to go to the center of power, where the image really meant something,” Magid recalls. “I went to the headquarters of police in Amsterdam and said, ‘I’m an artist and I want to cover your surveillance cameras with jewels.’” Unsurprisingly, the squad didn’t appreciate the leftfield request – until Magid changed tack, returning a few weeks later in a business suit and calling herself a representative of System Azure Security Ornamentation. “After six months of negotiations, not only did they let me do it, but they hired me. They paid me.” The camera’s flashy renovations drew attention to what had previously been an unnoticed feature of the urban environment. “Modernist architects thought that if you embellish something or you ornament something, then you killed its function,” Magid explains. “I saw ornamentation as a kind of weapon. By ornamenting this it was killing its function.”

The synthesis of these early experiments culminated with “Evidence Locker,” a project whose premise reads like the perfect set-up to a foreign thriller: five cops obsess over, track and collaborate with a mysterious stranger who knows she’s being watched. Concocted for the Liverpool Biennial, “Evidence Locker” was filmed by police and later edited by Magid as she wandered through the streets of Liverpool, one of the world’s most heavily surveilled metropolises. With over 242 active security cameras watching the city center, digital cameras record virtually all movement on the streets. “Many times I saw that the camera wasn’t watching, and I became dependent on the system,” Magid says. She became so emotionally invested that at times she would ask, “It was very emotional – ‘Why aren’t they watching me?’ They’d call later and say, ‘Oh Jill, we’re really sorry, but there was a murder and we had to deal with it.’”

The 31-day project – a “cycle of memory,” in Magid’s words – pushed the limits of the relationship between the artist and her conscious voyeurs. This relationship extended even to her access to the video footage which is typically erased after 31 days unless an official request letter is filed. Magid subsequently penned 31 requests, treating the bureaucratic missives like “love letters” to the police. The resulting 13 hours of surveillance footage tracks a red-coated Magid as she wanders, sits, smokes and consciously “performs” for her unseen observers.

Another project that examines the bond between individuals and omniscient authority is the 18-minute “Trust.” Wearing an earpiece, Magid closed her eyes and allowed an observing police officer to walk her safely through the city, using only his voice and the surveillance cameras to direct her. “What really developed was a relationship between me and the police. It went farther than I would have ever imagined. ‘Trust’ is when the system was transcended and people couldn’t believe that a system like that became this intimate, personal love story.”

Having since returned to New York, Magid is continuing her ongoing exploration of the way that systems of control and data – not only surveillance, but also forensics and the media – inform her own life. She’s turned a CAT scan of her skull into a molded facsimile of her “own” face in ecstasy (“Head”), and arranged for her ashes to be compressed into a diamond ring pending her death (“Auto Portrait Pending”). “I’m interested in desire,” she says. “Surveillance is about power, but underneath it all is this desire to feel safe. I’m not judging it. What I’m attracted to is the desire to feel safe, or that love lasts. Those poetic human desires are attracting me and I’m responding to them.”