Visual sniper Shepard Fairey canvasses the politics of pop agitprop and the graphic art of subversion.

Now take heed: A terrorist walks among us.

Deftly camouflaged with the nationalistic hues of Caucasian patriarchy and left-wing capitalist entrepreneurship, he bears a moniker equally disarming, at once whimsical and rustic-pastoral. His name is Shepard Fairey.

Granted, the man’s been touted as one the most revolutionary counterculture street artists of all time, a self-proclaimed punk rocker, populist and existential phenomenologist, labeled a Neo-Dadaist, Pop Artist, Bolshie Constructivist, Situationist and Agitpropagandist, an adbuster, guerilla marketer, Gen-Y designer and culture-jammer. And, though he’s been under arrest a total of 14 times (his latest laughably ironic stripe of defiance earned at the DNC in Denver last month for posting his widely popularized Obama renderings), Fairey’s carefully orchestrated acts of terrorism don’t actually constitute violations of any state or federal law, per se.

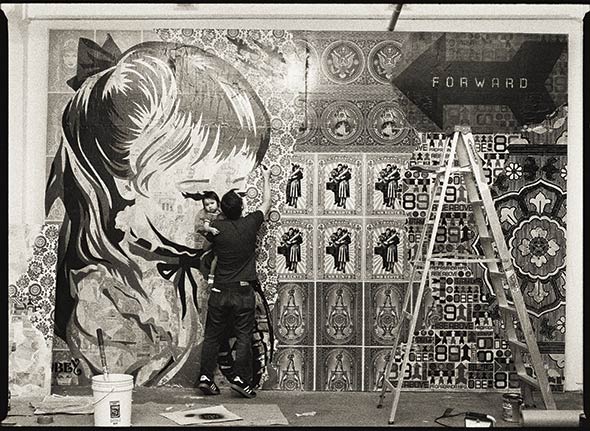

To shed some light, let’s travel back to Providence, RI, 1989—where it all began, so to speak. (But first, I must say, the precise originating factors in the birth, development and molding of a terrorist and the terrorist mind are virtually impossible to determine conclusively, and will escape scrutiny as an objective of this pogrom, ahem, program.) Deeply seditious stirrings (likely potent since inception) prodded the unraveling of the first few yarns of Fairey’s tale—a story home-spun and now internationally mythologized—tracing disruptive trails through the risd campus, and straight along any number of walls plastered with the crudely stenciled and Xeroxed stickers outlining the menacing visage of Andre the Giant.

Graced with an Orwellian “obey” directive, the graphic was mailed to co-conspirators everywhere with instructions to post in public spaces. Its vulnerability to mass-reproduction was no oversight. Pledging allegiance to diy-“Power to the People”-Punk philosophy, it asserted to all that even “with minimal resources you can make an impact,” says Shepard. Rapid spawning of devoted legions and worldwide viral dissemination ensued. What began as a pranksterist satire upon the increasingly obsequious skater culture paid to mainstream branding iconography, acquired a life of its own, evolving more blaring social dissonance. And a global counterculture street movement of historic proportion was born.

While Andre held the public spellbound, Fairey became enthralled with popular response—its enormity and furor, collectively; and its ability to psychologically probe perceptions, individually. These inspired critical sociological inquiries into the use of public space, and the individual’s interpretation of environmental imagery: “Most people think it’s a teaser campaign for something. How ingrained must the semiotics of commerce be, if that’s the immediate thing you think when looking at something?” Fairey asks. “I don’t have any political agenda, except to make people think.”

The Obey giant was utterly incoherent within a consumer culture context—an infuriatingly cryptic visual anomaly, blemishing the universally legible corporate logo landscape. And such an incursion, by sheer virtue of its inscrutability, “scares people,” Fairey explains. The poster campaign hadn’t merely piqued the public’s curiosity; it unleashed a deep-seated socio-cultural phobia worldwide, described by Roland Barthes’ Rhetoric of the Image (1964) as a “terror of the uncertain sign,” and denigrated by Michel Foucault as the “terrorism of obscurantism.”

In the brooding image, one encountered a consumer culture image with no wares for sale, and an authoritarian directive that lacked direction. With nothing to buy, and no one to obey, any relations between sign and signified are entirely obfuscated. By injecting the absurdist image into consumer culture’s corporate-coded visual terrain, Fairey, in essence, generated a mass crisis of semiotics, compelling people to abandon institutional assumptions and cultural codes, and tread the path of provisional perception—an erasure of bonds and celebration of disjuncture. Renegade of representational realism, the Andre image casts off the shackles of popular semiotic proscription, and roams, open to endlessly proliferating interpretation.

Pop culture’s unwitting induction of the Giant image into celebrity-hood signaled the success of Fairey’s first monumental counterculture coup—exaltation of a non-corporate, nonsensical image to the status of mass media icon. Fairey, in effect, infiltrated sacrosanct branding barriers, demolishing the myth of mass media dominion over cultural iconography.

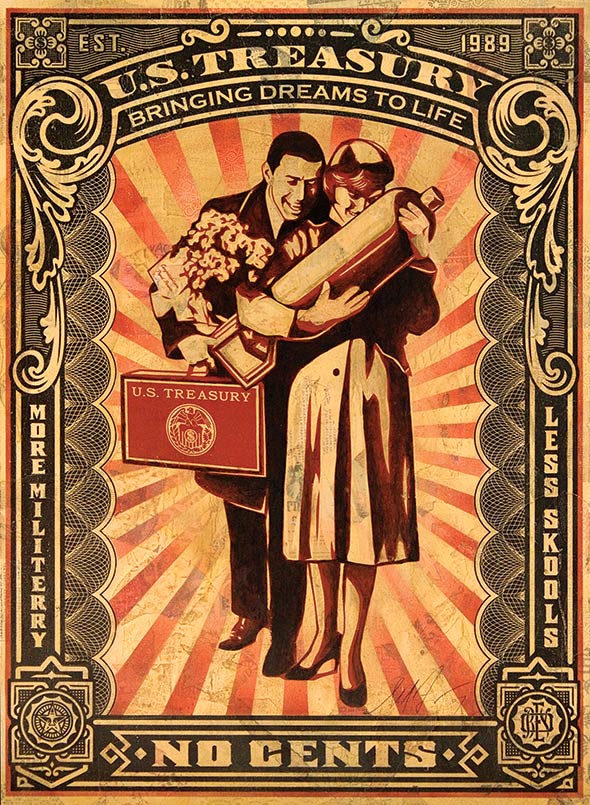

With the specter of war spilling onto the horizon, Fairey’s agenda began to multiply, yielding more overtly political work, and an intelligible semiology inscribed. Gallery exhibitions “Nineteeneightyfouria” and the “Duality of Humanity” recognize that language inevitability creeps into every image as we attempt to read them. Thus, word games are ubiquitous, where the image is either subverted by the text, or enacts a subversion, as in the “Obey Bush Hug Bombs” visual non-sequitur, contrasting patriotic, romanticizing imagery with accompanying text that censures a foreign policy of war and aggression. Framed within the red, black and white colors, bold typography and caricatured imagery of Communist propaganda posters, the U.S. president, soldiers, policemen—popular bastions of freedom and democracy—transmute into associative emblems of fascism, totalitarianism, repression. These détournements, where familiar icons are re-contextualized, result in a production of entirely new meanings, exposing the arbitrariness of the sign, its cultural and historical contingency.

Fairey’s posters banish any pre-conceived readings we may be inclined to impose, using familiar images whose recognizability is immediately subverted, their traditional readings rendered defunct, as in his Che Andre, the giant’s physiognomy in Che-like posture. In exposing one senseless conjunction after another, his creations ultimately invite us to ponder the senselessness of conjunction at large, tearing asunder carefully constructed systems of signs manufactured by the administration, corporate advertising and the media. “The issues are so much more nuanced,” says Fairey. The “E Pluribus Venom” show presented capitalism’s moral ambiguities: “I scattered bills of currency out onto the sidewalk—one side representing wage slavery, economic imperialism, oppression, the other side, empowerment through entrepreneurship, freedom of the press.” After all, Fairey reminds us, “I began all this by printing stickers.”

Meaningless stickers, which burgeoned into a wildly lucrative marketing company. Black Market media devotes itself to creating punk-aggressive, underground-attuned, commercially viable ad campaigns for the multi-national likes of Mountain Dew. But to the barrage of derision alleging him a once-upon-a-time revolutionary gone pop-cult rogue, Fairey retains his stoic cool. A populace born, bred and fed within the confines of mass media colonization should glimpse some truth in the fact that any truly effective anti-consumerist campaign inevitably produces some form of a consumable, and the anti-marketing marketing dilemma devolves into semiotic shadowboxing. So what’s the most effective means of hacking into the surface of ad culture? Make your own media, says Fairey. “I’m at a point in my life now where I can take an inside-outside approach, do things a little subversive, create, and integrate some into the mainstream.”

Perpetually battling ideological binaries, Fairey confesses, “I’m passed the point in my life, where I just wanted to sabotage everything around me.” With each revision and expansion upon mass media’s iconographic lexicon, he is reinventing the visual vocabulary of dissent. Most disconcerted by the proliferation of “hollow rhetoric” amongst political pundits and nominees, Fairey exhorts the public to “Please demand better, demand more.” Perhaps a dose of visual terrorizing is precisely what this convoluted global media landscape needs.

Take heart: A terrorist walks among us.

And some of us may see a bit more clearly because of it.

TEXT BY Felicia McCrossin

PHOTOGRAPHY BY Abbey Drucker